Kobayakawa Takakage was rightfully considered one of the most intelligent men of his era. Even Kuroda Kanbei, the celebrated strategist famed for his cunning—about whom people said he could outwit even a fox—admitted that Takakage was his equal in intellect, and at times even surpassed him. After the death of his father, Mōri Motonari, Takakage effectively governed the Mōri clan for many years while serving as advisor to his nephew, Mōri Terumoto.

Origins and Youth

The future commander was born in 1533 to Mōri Motonari and his wife, Myōkyū, as their third son. Motonari had many children, but those born to his lawful wife held a special place. Among them, the most notable were three: Mōri Takamoto, Kikkawa Motoharu, and Kobayakawa Takakage. A legend survives about them: Motonari handed his sons a bundle of three arrows and told them to break it—an impossible task. But each arrow could be broken easily on its own. In this way, he taught them the importance of unity.

Although similar legends appear in many cultures, it is known that Motonari truly did leave his sons instructions emphasizing mutual support. In childhood, Takakage was called Tokujōmaru, but at twelve he received his adult name and was adopted into the Takehara branch of the Kobayakawa clan. The head of that line, Kobayakawa Okikage, had died, and the twelve-year-old Tokujōmaru—related to Okikage’s wife as her cousin—became the new head of the clan.

Early Military Steps and the Unification of the Kobayakawa Clan

The Kobayakawa, like the Mōri, served the Ōuchi clan. As one of Ōuchi Yoshitaka’s commanders, Takakage quickly demonstrated outstanding ability and received praise, although he never formed a particularly close relationship with his lord.

In 1550 he also became head of the clan’s second branch, Numata-Kobayakawa. The head of that line, Kobayakawa Shigehira, was young, ill, and blind. Motonari married Takakage to Shigehira’s sister and effectively transferred authority to him. Thus Takakage united the two long-rival branches and became the sole head of the entire Kobayakawa clan.

However, the marriage produced no children. Rumor had it that the couple lived more like good friends, and Takakage showed little interest in either women or men. He therefore chose and adopted his younger brother Hidekane as his heir.

The Fall of the Ōuchi and the Rise of the Mōri

Meanwhile, strife broke out within the Ōuchi. Ōuchi Yoshitaka withdrew from politics, sparking uprisings among his vassals. He was replaced by Ōuchi Yoshinaga, who was completely controlled by Sue Harukata. The ensuing disorder weakened the clan, and Motonari took advantage of the situation. For a while he waited, keeping up the appearance of loyalty, but after securing alliances (notably with the Murakami clan), he declared independence from Ōuchi rule in 1554.

The Battle of Miyajima and the Defeat of Sue Harukata

Sue Harukata marched against the Mōri with 30,000 men. Motonari, commanding fewer troops, realized a direct battle would be hopeless. He devised a daring plan involving the island of Miyajima—the sacred site of the Itsukushima Shrine, where war had never been brought before. Motonari seized the island with a small force, provoking Sue to attack. Sue took Miyajima—only to fall into the trap.

On the night of October 16, Kobayakawa Takakage executed a feint with his fleet, forcing Sue to shift troops to a false landing point. At that moment, Motonari and the Murakami attacked from the rear. Takakage circled the island, landed by the shrine gates, and crushed the enemy. Sue Harukata committed suicide, and the Mōri emerged as the dominant power in western Japan.

The “Two Rivers” and Takamoto’s Death

In 1559, Ōtomo Sōrin captured the castle of Moji, but the Mōri fleet under Takakage retook it. That same year Motonari retired, passing leadership to his eldest son, Takamoto. Takakage and his brother Motoharu became his pillars. Motoharu focused on military matters, Takakage on politics. Together they were known as the “Ryōkawa”—“Two Rivers.”

But in 1563, Takamoto suddenly died, prompting rumors of assassination. Motonari punished those he believed responsible, though they were later proven innocent. Takamoto’s son, Terumoto, became clan head.

New Wars and the Loss of Alliances

In 1571, the Mimura clan—Mōri vassals in Bizen—were attacked by Urakami Munekage. Takakage went to aid them, but the Murakami unexpectedly sided with Urakami, forcing Takakage to retreat. That same year Motonari died, and the conflict ground to a halt.

In 1574, Urakami gained support from Oda Nobunaga, and the disillusioned Mimura defected to the Oda side. Takakage formed an alliance with Ukita Naoie, retook the Mimura lands, and forced Mimura Mototika to commit seppuku for treason.

Alliance Against Nobunaga and the Naval Battles

In 1576, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki quarreled with Nobunaga and called on the Mōri to join an alliance that included Uesugi Kenshin, Takeda Katsuyori, and the monks of Ishiyama Honganji. The Mōri agreed, seeing Oda expansion as a threat.

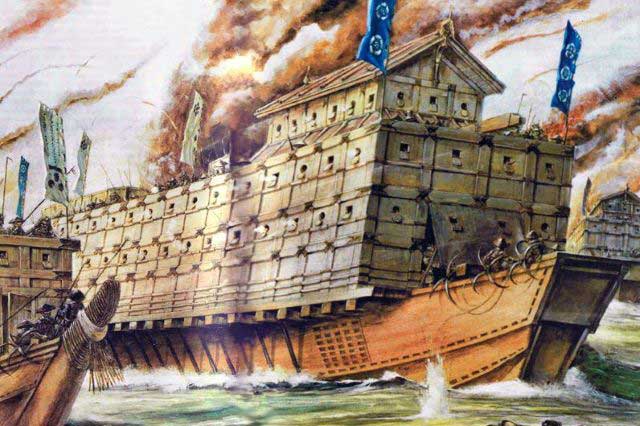

Murakami Takeyoshi, head of the Murakami clan, also drew closer to the Mōri. Their combined fleet under Takakage defeated the forces of Kuki Yoshitaka, who attempted to block the river near Ishiyama Honganji. But two years later the Oda fleet sailed again. This time Kuki introduced the ōatakebune—heavy wooden ships with metal plating. Despite technical flaws, they allowed Nobunaga to claim victory and continue pushing into Mōri territory.

Hideyoshi’s Campaign and the “Water Siege” of Takamatsu

Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi was assigned to subdue the Mōri. His successes were rapid, and by 1580 the Mōri had lost Harima and Inaba. The key point of resistance was Takamatsu Castle, commanded by Takakage’s vassal, Shimizu Muneharu. Unable to take the fortress by force, Hideyoshi built a dam to divert the river and flood the castle.

The Mōri rushed to aid Shimizu, but the rising waters created a vast artificial lake that made battle impossible. Takakage opened negotiations, but Hideyoshi—expecting Oda Nobunaga’s army under Akechi Mitsuhide to arrive soon—refused peace.

But Mitsuhide suddenly betrayed Nobunaga and killed him. Hideyoshi learned this before the Mōri and immediately sought peace. He agreed to return three provinces to the Mōri in exchange for the castle and Shimizu Muneharu’s seppuku. Takakage rejected these terms outright. Hideyoshi then spoke directly to Shimizu, convincing him that the Mōri were doomed. Shimizu agreed to die to save his men and secure the provinces. He committed seppuku on a boat at the center of the lake.

The Brothers’ Dispute and Alliance with Hideyoshi

When the Mōri learned of Nobunaga’s death, Kikkawa Motoharu demanded immediate vengeance and war against Hideyoshi. Takakage intervened, arguing such action would spark another devastating conflict and nullify Shimizu’s sacrifice. The Mōri remained neutral, but later—once it became clear Hideyoshi would rule Japan—they joined him.

Takakage took part in the conquest of Shikoku, receiving Iyo Province and establishing his residence at Yuzuki Castle. The Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis noted that under his rule, peace and order prevailed in Iyo. Takakage also joined the Kyushu campaign but refused the lands offered to him, preferring to remain a loyal vassal of Mōri Terumoto. At Hideyoshi’s request, he took charge of Chikuzen Province and built Najima Castle—the future base for the Korean invasions.

Takakage’s Character and the Story of Kanehime

Terumoto respected and feared his uncle, for Takakage was a strict yet caring mentor. A telling example is the story of the concubine Kanehime. She was the daughter of a Mōri vassal, Kodama Motoyoshi, and Terumoto fell in love with her. Her father, learning of this, married her off to Nobu Sugimoto. Terumoto abducted her, and Motoyoshi complained to Hideyoshi: a married woman had been taken as a concubine, violating the law. Takakage resolved the issue decisively—he killed Sugimoto, declaring, “One may not take a married woman as a concubine, but a widow is acceptable.” The complaint ended there.

The Korean Campaign

In 1592, Hideyoshi launched his invasion of Korea. Takakage commanded the 6th Division and led 10,000 soldiers. His advance into Jeolla Province met fierce resistance, forcing him to withdraw. With the arrival of the Chinese army, the Japanese position worsened. Takakage proposed a plan: stage a retreat, lure the enemy into a muddy lowland, and strike in coordination with Katō Kiyomasa. The plan succeeded—the Chinese bogged down, took losses, and the Japanese withdrew in good order. Peace negotiations began, and most of the army returned home.

The Adoption of Hideaki and Its Consequences

In 1594, Hideyoshi suggested that Terumoto adopt his nephew, Hideaki. Takakage opposed the idea, understanding how easily an adopted heir could displace legitimate successors. But refusing Hideyoshi was impossible. With Katō Kiyomasa as intermediary, Takakage arranged to adopt Hideaki himself. Hideaki eventually inherited the Kobayakawa clan—and later earned infamy for his betrayal at the Battle of Sekigahara.

The Council of Elders and Takakage’s Final Years

In 1595, Hideyoshi established a Council of Elders to govern Japan after his death and protect his son, Hideyori. The council included Maeda Toshiie, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Ukita Hideie, Uesugi Kagekatsu, and Kobayakawa Takakage. Hideyoshi said: “If the west of Japan is entrusted to Kobayakawa, there is nothing to fear.”

Kobayakawa Takakage died on July 26, 1597. His place on the council was taken by Mōri Terumoto, who was left without the “Two Rivers,” and thus without reliable advisors. This marked the beginning of the Mōri clan’s decline.

Legacy of Kobayakawa Takakage

Takakage was buried at Beisanji Temple in Hiroshima. His grave remains preserved as a protected cultural site, as does the temple itself—the traditional burial place of the Kobayakawa family. Takakage became a figure in many literary and artistic works. Though he never achieved the fame of Toyotomi Hideyoshi or Oda Nobunaga, his role in Japanese history was significant.

See also

-

Yamagata Masakage

Masakage was one of Takeda Shingen’s most loyal and capable commanders. He was included in the famous list of the “Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen” and also belonged to the inner circle of four especially trusted warlords known as the Shitennō.

-

Yagyu Munenori

Yagyū Munenori began his service under Tokugawa Ieyasu while his father, Yagyū Muneyoshi, was still at his side. In 1600, Munenori took part in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara. As early as 1601, he was appointed a kenjutsu instructor to Tokugawa Hidetada, Ieyasu’s son, who later became the second shogun of the Tokugawa clan.

-

Yagyu Muneyoshi

A samurai from Yamato Province, he was born into a family that had been defeated in its struggle against the Tsutsui clan. Muneyoshi first took part in battle at the age of sixteen. Due to circumstances beyond his control, he was forced to enter the service of the Tsutsui house and later served Miyoshi Tōkei. He subsequently came under the command of Matsunaga Hisahide and in time became a vassal first of Oda and later of Toyotomi.

-

Endo Naozune

Naozune served under Azai Nagamasa and was one of the clan’s leading vassals, renowned for his bravery and determination. He accompanied Nagamasa during his first meeting with Oda Nobunaga and at that time asked for permission to kill Nobunaga, fearing him as an extremely dangerous man; however, Nagamasa did not grant this request.

-

Hosokawa Sumimoto

Sumimoto came from the Hosokawa clan: he was the biological son of Hosokawa Yoshiharu and at the same time the adopted son of Hosokawa Masamoto, the heir of Hosokawa Katsumoto, one of the principal instigators of the Ōnin War. Masamoto was homosexual, never married, and had no children of his own. At first he adopted Sumiyuki, a scion of the aristocratic Kujō family, but this choice provoked dissatisfaction and sharp criticism from the senior vassals of the Hosokawa house. As a result, Masamoto changed his decision and proclaimed Sumimoto as his heir, a representative of a collateral branch of the Hosokawa clan that had long been based in Awa Province on the island of Shikoku. Almost immediately after this, the boy became entangled in a complex and bitter web of political intrigue.

-

Honda Masanobu

Masanobu initially belonged to the retinue of Tokugawa Ieyasu, but later entered the service of Sakai Shōgen, a daimyo and priest from Ueno. This shift automatically made him an enemy of Ieyasu, who was engaged in conflict with the Ikkō-ikki movement in Mikawa Province. After the Ikkō-ikki were defeated in 1564, Masanobu was forced to flee, but in time he returned and once again entered Ieyasu’s service. He did not gain fame as a military commander due to a wound sustained in his youth; nevertheless, over the following fifty years he consistently remained loyal to Ieyasu.

-

Honda Masazumi

Masazumi was the eldest son of Honda Masanobu. From a young age, he served Tokugawa Ieyasu alongside his father, taking part in the affairs of the Tokugawa house and gradually gaining experience in both military and administrative matters. At the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Masazumi was part of the core Tokugawa forces, a clear sign of the high level of trust Ieyasu placed in him. After the campaign ended, he was given a highly sensitive assignment—serving in the guard of the defeated Ishida Mitsunari, one of Tokugawa’s principal enemies—an obligation that required exceptional reliability and caution.

-

Hojo Shigetoki

Hōjō Shigetoki, the third son of Hōjō Yoshitoki, was still very young—only five years old—when his grandfather Tokimasa became the first member of the Hōjō clan to assume the position of shogunal regent.