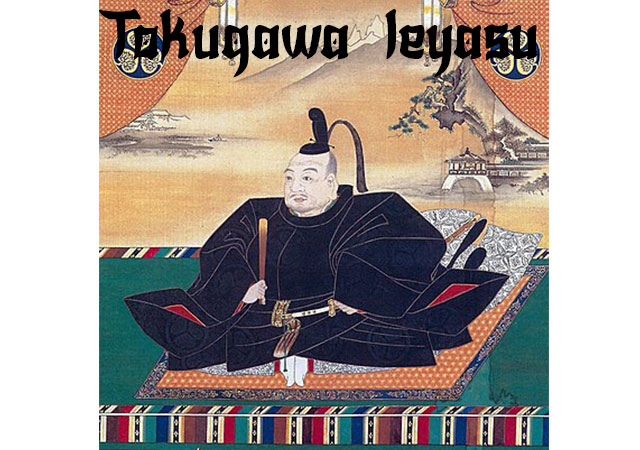

In 1603, the head of the Tokugawa Clan proclaimed himself shogun, thus starting the rule of the clan in Japan. Having set up a complete military dictatorship of the samurai by the 17th century, the Tokugawa Clan managed to completely centralize and augment its authority.

The Tokugawa’s strong central authority put an end to feudal fragmentation and resulted in the minimization of wars between feudal lords. Now, samurai served only to put down peasant and civilian revolts.

As for the samurai’s social status, by then, they were at the top since the shogunate closely monitored the estate system of power and subordination. The following hierarchy system was developed: samurai – peasants – artisans – merchants. Of course, the samurai ranked the highest as they were a support of the Tokugawa regime and were considered the core of the nation and the best people. There was a separate group of court aristocracy. Even though officially, it ranked above samurai, in fact, it was deprived of any political and economic power.

Although the samurai estate was considered single on paper, the Tokugawa regime clearly divided the samurai by their ranks. In addition to the gokenin, the existing samurai of the highest military nobility, feudal lords whose status depended on the size of their lands, a new samurai class of hatamoto was established. Hatamoto, translated from Japanese, means the standard-bearer, and this class of samurai was directly subordinate to the military government and the shogun.

The hatamoto samurai had the powers that the gokenin did not have. They had the right to a private audience with the shogun and could enter the building from the main entrance. In the event of war, the hatamotos formed the shogun’s army and were part of the shogun’s administration. According to the social hierarchy, the hatamoto and gokenin samurai were followed by baishin (a vassal of vassal), and the lowest samurai estate was ashigaru, ordinary soldiers.

Separately from the samurai estates, there were ronin. Ronin is a samurai who has let his master die or has been cast out from the clan or has left the suzerain voluntarily, for example, for a blood feud, and could return to service after. Many ronin who were unwilling or unable to be engaged in farming, handicrafts or trade, since they had no livelihood, gathered in gangs and robbed small villages or bystanders on the road. Ronin often became hired killers who would stop at nothing for money.

By the 17th century, the number of samurai reached approximately 400,000 and about two million together with their families. Japan’s population itself at that time was about 16 million.

The number of samurai varied by region, depending on the wealth and the size of the lands of the feudal lords. This means that the richer the feudal lords in a particular province are, the more samurai lived there.

The majority of the samurai did not own lands and were rewarded rice for serving. The unit of measurement of this payment was koku, rice ration. The extent of the payment depended, of course, on the samurai status. With the received rice, the samurai could keep their families, buy clothes, household items, etc. In fact, it was the only source of income since the Tokugawa shogunate prohibited samurai to be engaged in crafts, trade, and usury, considering it shameful for them. However, the samurai were exempt from taxes.

As for the samurai’s conduct during the Tokugawa shogunate’s rule, they were to be guided by the “Buke hatto” code written by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1615. The code listed the rules of samurai’s conduct on service and at home, how samurai must treat their weapons, serve the feudal lords and address the feudal lords whom they serve, what clothes must be worn by each samurai class, what literature they must read, and it also explained marriage matters.

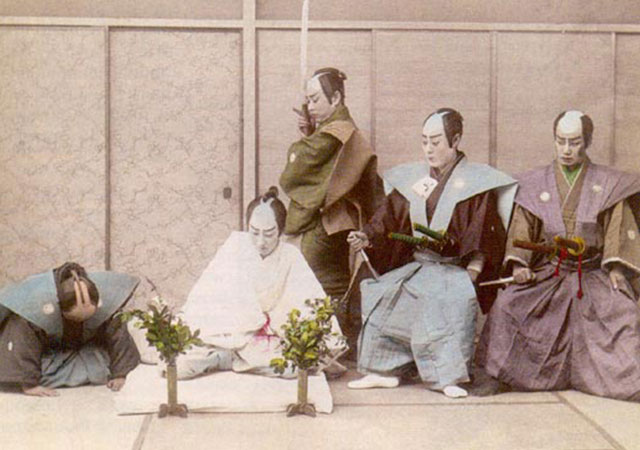

In addition to the rules and duties, the Buke hatto strictly protected the samurai’s honor. One of the articles of the code stated that a samurai could kill a peasant or citizen on the spot if they insulted him. Peasants, once they notice a samurai, had also to take off their hats and go on their knees, no matter where they were – on the roadside or at work. Every such meeting with a samurai could have ended in death for a peasant. A peasant or citizen could also be punished for that a samurai could consider it excessive. However, a samurai could also be punished by death for violations that would have not resulted in death for a peasant. For example, for disobeying an order or breaking their promises, samurai had to commit hara-kiri.

The reign of the Takugawa Family was a period of supreme development for samurai. During this period, the samurai’s culture, customs and rules were fully developed.

See also

-

Yamagata Masakage

Masakage was one of Takeda Shingen’s most loyal and capable commanders. He was included in the famous list of the “Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen” and also belonged to the inner circle of four especially trusted warlords known as the Shitennō.

-

Yagyu Munenori

Yagyū Munenori began his service under Tokugawa Ieyasu while his father, Yagyū Muneyoshi, was still at his side. In 1600, Munenori took part in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara. As early as 1601, he was appointed a kenjutsu instructor to Tokugawa Hidetada, Ieyasu’s son, who later became the second shogun of the Tokugawa clan.

-

Yagyu Muneyoshi

A samurai from Yamato Province, he was born into a family that had been defeated in its struggle against the Tsutsui clan. Muneyoshi first took part in battle at the age of sixteen. Due to circumstances beyond his control, he was forced to enter the service of the Tsutsui house and later served Miyoshi Tōkei. He subsequently came under the command of Matsunaga Hisahide and in time became a vassal first of Oda and later of Toyotomi.

-

Endo Naozune

Naozune served under Azai Nagamasa and was one of the clan’s leading vassals, renowned for his bravery and determination. He accompanied Nagamasa during his first meeting with Oda Nobunaga and at that time asked for permission to kill Nobunaga, fearing him as an extremely dangerous man; however, Nagamasa did not grant this request.

-

Hosokawa Sumimoto

Sumimoto came from the Hosokawa clan: he was the biological son of Hosokawa Yoshiharu and at the same time the adopted son of Hosokawa Masamoto, the heir of Hosokawa Katsumoto, one of the principal instigators of the Ōnin War. Masamoto was homosexual, never married, and had no children of his own. At first he adopted Sumiyuki, a scion of the aristocratic Kujō family, but this choice provoked dissatisfaction and sharp criticism from the senior vassals of the Hosokawa house. As a result, Masamoto changed his decision and proclaimed Sumimoto as his heir, a representative of a collateral branch of the Hosokawa clan that had long been based in Awa Province on the island of Shikoku. Almost immediately after this, the boy became entangled in a complex and bitter web of political intrigue.

-

Honda Masanobu

Masanobu initially belonged to the retinue of Tokugawa Ieyasu, but later entered the service of Sakai Shōgen, a daimyo and priest from Ueno. This shift automatically made him an enemy of Ieyasu, who was engaged in conflict with the Ikkō-ikki movement in Mikawa Province. After the Ikkō-ikki were defeated in 1564, Masanobu was forced to flee, but in time he returned and once again entered Ieyasu’s service. He did not gain fame as a military commander due to a wound sustained in his youth; nevertheless, over the following fifty years he consistently remained loyal to Ieyasu.

-

Honda Masazumi

Masazumi was the eldest son of Honda Masanobu. From a young age, he served Tokugawa Ieyasu alongside his father, taking part in the affairs of the Tokugawa house and gradually gaining experience in both military and administrative matters. At the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Masazumi was part of the core Tokugawa forces, a clear sign of the high level of trust Ieyasu placed in him. After the campaign ended, he was given a highly sensitive assignment—serving in the guard of the defeated Ishida Mitsunari, one of Tokugawa’s principal enemies—an obligation that required exceptional reliability and caution.

-

Hojo Shigetoki

Hōjō Shigetoki, the third son of Hōjō Yoshitoki, was still very young—only five years old—when his grandfather Tokimasa became the first member of the Hōjō clan to assume the position of shogunal regent.