The Hara-Kiri Essence

The hara-kiri rite, or as it is also called seppuku, is closely related to the bushido samurai philosophy. This custom originated in the early period of Japanese feudalism. It was the benefit of the samurai only who were proud to have free control of their lives, to have the moral courage and show contempt for death with seppuku.

The word hara-kiri is literally translated from Japanese as “cutting the stomach”, where “hara” is the abdomen and “kiri” is to cut. The Japanese chose the stomach because, according to Zen Buddhist philosophy, it is the human’s central area and the seat of life. Thus, for the Japanese, the stomach was an area where they existed emotionally and, by cutting it, the samurai showed the honesty of their intentions, thoughts and aspirations. For the samurai, seppuku was an excuse for themselves before heaven and people and had more spiritual sense, rather than suicide.

When the Rite Emerged

The disemboweling rite was found among some peoples of Siberia and East Asia, one of them was the Ainu people who lived in the northeast Japanese islands. The Japanese fought with the Ainu people for lands for a long time and eventually adopted the rite from them. However, the Japanese changed its meaning. Among the Ainu and other peoples, it was sacrificial, they cut their stomachs voluntarily to sacrifice to the gods.

Originally, hara-kiri was not common among the Japanese. It began to develop among the military settlers who lived on lands from the Ainu people and eventually evolved into a samurai class. And it is quite natural that this rite began to develop among people who constantly bore weapons and were always on alert.

In the 9th century, starting from the Heian period, the seppuku became the samurai’s custom, and by the end of the 12th century, during the Taira-Minamoto War, hara-kiri became widespread. Since then, the number of suicides continued to rise.

When Hara-Kiri Was Performed

There were several reasons for the samurai’s suicidal rite. This could be punishment for disobedience or non-fulfillment of orders of their shoguns or feudal lords, as well as for acts disgraceful to the samurai.

The samurai often used hara-kiri as a sign of protest to show that they disagreed with the impossible orders of their master or some other injustice affecting the samurai’s honor.

The samurai could also perform hara-kiri in the wake of their master’s death. Initially, it was called “oibara” or “tsuifuku”, and later, this custom was renamed “junshi”. This suicide goes back to ancient Japan when, together with a deceased man of family, his servants were buried. This custom was then abolished, and the servants were replaced with clay figurines. Over time, this custom however was transformed and became popular among samurai again. The samurai could voluntarily take their lives following their masters by performing the hara-kiri rite.

It was not only the samurai who committed suicide but also their wives. The reason for hara-kiri could be their husband’s death, if their husband went back from their words, or if their husband’s pride was hurt. It was considered a shame if the wife could not perform hara-kiri if necessary. However, unlike the samurai, their wives committed suicide not by cutting their stomachs. They slit their throats or stabbed them in their hearts with a special dagger called kaiken which was given as a wedding gift by their husbands. They could also use a short sword, which was given to each samurai’s daughter on the day of the majority.

Samurai and their daughters were taught to commit suicide from their childhood. Instructors in special schools showed and explained how to start and complete seppuku, how to cut a stomach or how to cut the neck vein and stab yourself in your heart correctly.

How the Seppuku Rite Was Performed

The rules and the ceremony of the seppuku rite were developed over a long time. It was formalized and legitimized during the reign of the Ashikaga shogunate from 1333 to 1573. The rite was finally formalized, complicated and began to be applied officially by the court as a punishment for the crime committed by a samurai during the Edo period.

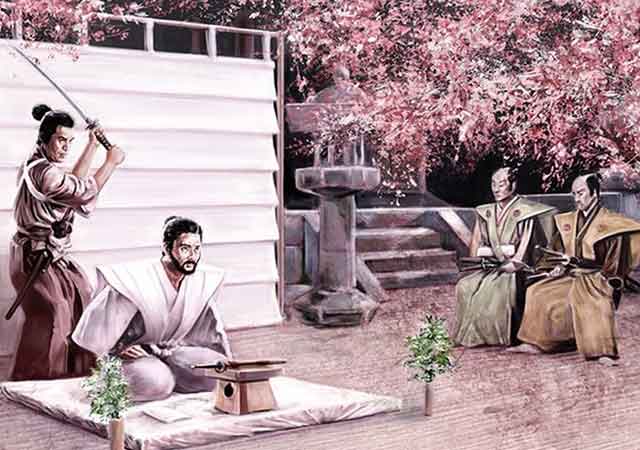

During this period, the rite also involved a second who had to always witness the official seppuku ceremony. The second had to cut off the samurai’s head after he had slit his stomach, thereby sparing the samurai pain. The head was also cut off so that the samurai, being in mortal agony and losing self-control, would not start screaming or fall on his back, thereby disgracing his name.

As per the code written during the Tokugawa shogunate reign, there were persons appointed to officiate the seppuku ceremony. They arranged the ceremony and attended it. The Tokugawa authorities decided that death by seppuku is honorable and that this benefit is available to the samurai only.

The location for the seppuku rite was chosen according to the samurai’s status in society. For the shogun’s friends, it was performed in the palace, for the lower-ranked samurai, it was performed in the garden of the house of the ruler who took care of the samurai who committed suicide. Hara-kiri could also be performed in the temple if a samurai decided to commit suicide during his journey.

Seppuku was usually performed when sitting, while clothes were placed under the samurai’s knees so that the samurai would not fall on his back. Then the performing samurai cut his stomach with a special knife called tanto which was considered a family value and was kept at home on a sword stand. If the knife was not available at the moment, then the rite was carried out using the second small sword called wakizashi. Sometimes, the samurai used a katana; they took it by a blade wrapped in paper.

The direction and number of cuts depended on the school and the samurai who committed hara-kiri. They could cut their stomachs from left to right, from left to right and upward, X-like, upward and to the left, etc.

Previously, a samurai performing seppuku had to slice his stomach so as to show his intestines to those present. Then the ceremony was simplified and the samurai only had to cut their stomachs and the second cut off their heads. All those who performed the suicidal rite were buried together with the weapon that the rite was performed with.

How Hara-Kiri Differs from Seppuku

Hara-kiri and seppuku mean the same. Their only difference is the following: The word hara-kiri was used in everyday life and carried out by samurai in solitude. And the word seppuku was the official name of the rite, specified in the documents and was performed when officials and a second are around.

See also

-

Kubota Castle

The founder of the castle is considered to be Satake Yoshinobu (1570–1633). Yoshinobu was one of the six great generals of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. During the Odawara Campaign of 1590, he took part in the siege of Oshi Castle under the command of Ishida Mitsunari, with whom Yoshinobu developed a good relationship.

-

Kavanhoe Castle

Kawanoe Castle is located on the small Wasi-yama hill near the port area of the Kawanoe district in the city of Shikokuchuo, occupying a central position along the northern coast of Shikoku Island. Kawanoe was also known as Butsuden Castle. The term “butsuden” in Japan refers to temple halls, and for this reason it is believed that a Buddhist temple once stood on the site before the castle was built. Due to its location at the junction of four provinces on Shikoku Island, Kawanoe held significant strategic importance and was repeatedly targeted by rival forces seeking military control over the region.

-

Yokote Castle

The founder of the castle is considered to be the Onodera clan. The Onodera were originally a minor clan from Shimotsuke Province and served Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), the founder of the first shogunate. The Onodera distinguished themselves in battle against the Fujiwara clan of the Ōshū branch and were rewarded with lands around Yokote. Around the 14th century, the Onodera moved to Yokote as their permanent residence. Their original stronghold was Numadate Castle, but after a series of clashes with the powerful Nambu clan, they relocated their base to the site of present-day Yokote Castle. It was likely during this time that the first fortifications appeared at the castle.

-

Wakayama Castle

Wakayama Castle was built in 1585, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered his uterine brother, Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hidenaga, to construct a castle on the site of the recently captured Ota Castle. The purpose of this construction was to secure control over the likewise newly conquered Province of Kii. Following an already established tradition, Hidenaga entrusted the project to his castle-building expert, Todo Takatora. Takatora carefully inspected the future castle site, personally drew up several designs, created a model of the planned castle, and took part in the work of laying out the grounds (nawabari). For the construction he brought in more than 10,000 workers and completed the large-scale project within a single year, which was considered extremely fast by the standards of the time.

Toyama Castle

Toyama Castle is located almost in the very center of the former province of Etchū and is surrounded by a wide plain with a large number of rivers. The very first castle on the banks of the Jinzu River was built in 1543 by Jimbo Nagamoto. The Jimbo clan were vassals of the Hatakeyama clan and governed the western part of Etchū Province. The eastern part of the province belonged to their rivals, the Shiina clan, who were also Hatakeyama vassals. Beginning in the 15th century, the influence of the ancient Hatakeyama clan gradually weakened, and as a result, the Jimbo and the Shiina fought constant wars for control of the province. Meanwhile, the forces of the Ikkō-ikki movement periodically intervened, helping first one side and then the other.

Takada Castle

During the Sengoku period, the lands where Takada Castle would later be built were part of Echigo Province and were controlled by the Uesugi clan.

Kishiwada Castle

The celebrated 14th-century military commander Kusunoki Masashige (1294–1336), who owned extensive lands south of what is now the city of Osaka, ordered one of his vassals, Kishiwada Osamu, to build a fortified residence. This order was carried out around 1336. These fortifications became the first structures on the site of what would later become Kishiwada Castle. From the beginning, the castle stood in a strategically important location—roughly halfway between the cities of Wakayama and Osaka, south of the key port of Sakai. Because of this position, it changed hands several times during periods of warfare.

Kaminoyama Castle

Kamino-yama Castle stood at the center of an important logistics hub, in the middle of the Yonezawa Plain, which served as the gateway to the western part of the Tohoku region. Roads connecting the Aizu, Fukushima, and Yamagata areas intersected here.