After the Tokugawa regime fell in 1869, the new imperial government of Japan began introducing bourgeois economic and political reforms. They first struck at the feudal system and the samurai estate, forcing the large feudal lords to relinquish their old rights in controlling clans.

The next stage in the struggle against the feudal system was that feudal princes were removed from governing their provinces. In 1871, Japan abolished being divided into principalities and introduced a new administrative division into prefectures. Thus, the princes who had previously ruled as hereditary governors were completely removed from their authority. Now, the new prefectures were governed by officials. Also, the land right of the large feudal lords was abrogated, and the lands became the property of the bourgeoisie.

In 1872, the old Tokugawa estate division was abolished. It was replaced by the new one, which divided the entire population of Japan into three classes: the Kazoku, representatives of military and court nobility; the Shizoku, former military nobility; common people which included peasants, citizens, craftsmen, etc. Officially, all estates had equal rights, and peasants received the right to have a family name. The only exception to these estates was the imperial family.

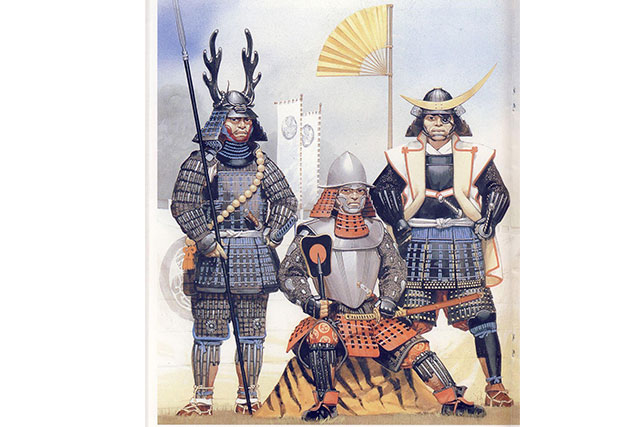

These reforms were followed by the military ones. The Japanese army began to be formed based on universal conscription. The samurai took this as a violation of their social rights. In fact, the army based on universal conscription, which included peasants and townspeople, meant that samurai were officially abrogated as a military estate. However, in the new European-like army, command spots were given only to samurai belonging to the Chōshū (who served in the army) and Satsuma (who served in the navy) Clans. There were about forty thousand of them. These two clans were closely related to the Japanese monarchy and counterweighted the samurai who could not forge their own paths in the new conditions, guarded the former feudal standards and opposed the imperial authority.

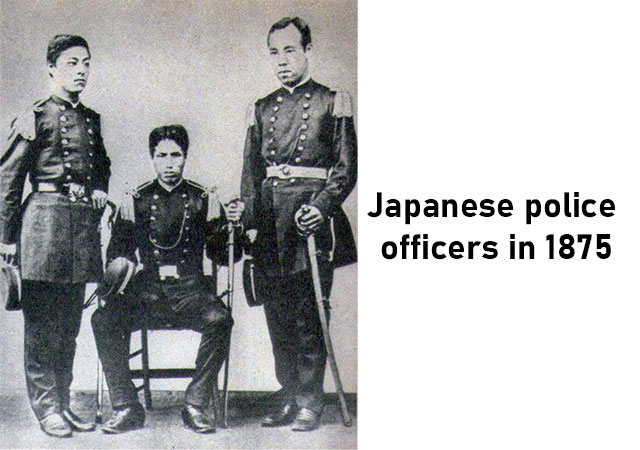

In addition to forming the universal conscription army, the samurai were also dissatisfied with the pension they were entitled to. Under the new rules, it was replaced by a lump-sum payment, half of which was interest-bearing securities issued by the government. They were also dissatisfied with the revocation of the right to bear swords in 1876, only the military officials and the police had it. The weapons also remained part of the court’s clothing.

Therefore, many samurai joined the police as they were allowed to bear weapons and this was not considered to be shameful. At the same time, people, knowing that the police mostly included former samurai, routinely treated them like they did during the Tokugawa reign.

Of course, all these new reforms were unacceptable to the samurai class, and they demanded to return to the former feudal system and remove bourgeois reforms. However, despite revolts and armed uprisings by samurai, capitalist reforms continued to be introduced.

The new Japanese army had the features specific to the feudal armies of samurai. Mainly, these were ideological features. The basic ideological and moral education of the soldiers of the new army was based on the bushido samurai code, which was amended to correspond to the new age. The only difference between the new code and the former one was that all conscripts were now taught to faithfully serve and sacrifice themselves not for the shogun but for the Emperor and Japan. This was previously required only from the samurai.

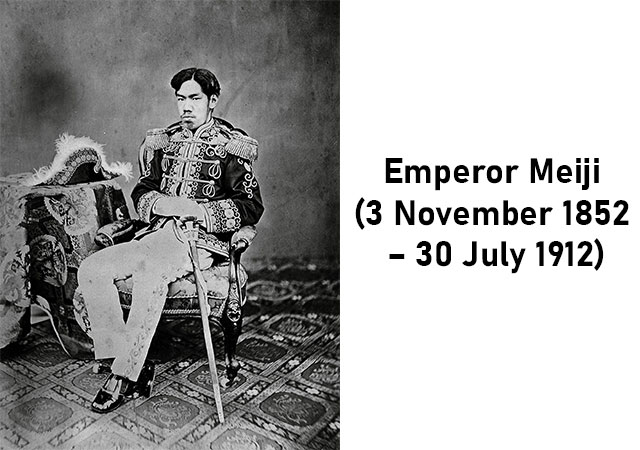

Even though soldiers in the new imperial army were educated by bushido canons, there was no room for such punishment and rite as hara-kiri. Hara-kiri was abolished after 1868. However, people continued to voluntarily end their lives in this way. And they were taken with tacit approval in certain circles, which gave a sense of greatness and glory to the persons who performed the rite. An example of how long the rite has been popular in Japan is the case of General Nogi and his wife’s hara-kiri after the death of Emperor Mutsuhito in 1912. The voluntary death of the General and his wife was considered the principle of being faithful in the usual samurai manner.

Even though the new imperial authority abrogated the samurai estate and recruited people into the army by universal conscription, the samurai continued to influence society. This was especially true for the army, where for many years until the end of World War II, soldiers were educated by the bushido rules, complete devotion and sacrifice in the name of the emperor and Japan.

See also

-

The Fall of the Samurai Age

By the beginning of the 18th century, Japan had a strong centralized government led by the Tokugawa Clan. Thereby, military conflicts between feudal lords were over and economic reforms resulted in the start of capitalism development.

-

The Rise of Samurai in Japan

In 1603, the head of the Tokugawa Clan proclaimed himself shogun, thus starting the rule of the clan in Japan. Having set up a complete military dictatorship of the samurai by the 17th century, the Tokugawa Clan managed to completely centralize and augment its authority.

-

The Emergence of the Samurai as a Military Estate

Feudal fragmentation, internecine war, and power struggles between large feudal lords resulted in the fact that, by the 12th century, the samurai finally consolidated themselves as a military class.

Read more: The Emergence of the Samurai as a Military Estate

-

How the Samurai Emerged

From the old Japanese language, the word samurai means the following: to serve a high-ranking person, to protect the master, to serve the master. The hieroglyph for the word samurai was borrowed from Chinese and reads as "Ji". In the Chinese language, this hieroglyph refers to the people guarding Buddhist temples. Also, to denote the word samurai, the hieroglyph "bushi" is used. The character means a warrior, a fighter.