Along with the development of feudalism in Japan and the advent of the samurai, the doctrine of "Zen" was born and developed. "Zen" or "Zenshu" is one of the directions in Buddhism. Subsequently, Zen would become the most popular and influential teaching among the samurai.

The Buddhist monk Bodhidharma is considered the founder of Zen. He began preaching in India and China. At the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century, the teaching penetrated into Japan. It happened thanks to two Buddhist monks Eisai and Dogen. The word "Zen" in Japanese means: silent contemplation, mastery of spiritual and external forces to achieve enlightenment.

The teachings of Zen became popular among the samurai because its foundations taught everything that a good warrior needs. The teaching said that work on oneself is constantly needed, it develops the ability to find the essence of any problem, focus on it and go towards your goal, no matter what.

The prostate also contributed to the spread of the teachings among the samurai. Zen denied any written language and the samurai did not have to read various religious books. But for propaganda, supporters of the teaching used Buddhist books and texts. Samurai had to delve into the teachings of Samumu or with the help of a mentor.

Zen helped develop the samurai's will, composure, and self-control, which were necessary skills for a good warrior. A very important skill for a samurai was not to flinch in the face of unexpected danger and to be able to maintain clarity of mind and be aware of his actions and actions. According to the teachings, the samurai had to have iron willpower, go straight to the enemy and kill him, without looking back or to the side. At the same time, Zen taught to be restrained and imperturbable in all situations, and a professing Zen Buddhist should not even pay attention to insults. In addition to self-control, the teachings of Zen instilled in the samurai unquestioning obedience to their commander and master.

An attractive factor for the samurai in the teaching was that Zen Buddhism recognized life in the existing world not as a reality, but as just an appearance. Life for Zen is only an ephemeral and illusory representation of "Nothing". Life is given to people for a while. And as the main religion of the samurai, Zen Buddhism taught not to cling to life and not be afraid of death. A true warrior had to despise death.

The religion of the samurai, which considered life to be illusory and impermanent, connected everything transient with the concept of beauty. A short-term, short-lived, short period of time was clothed in a special aesthetic form. From here comes the love of the samurai to watch the cherry blossoms and how the petals of this tree fall. This also includes the evaporation of the race in the morning after sunrise and other similar things. In fact, it follows from this that the shorter the life of a samurai, the more beautiful it is. A short but bright life was considered especially beautiful. This concept formed the Japanese warriors' lack of fear of death and the ability to die.

The concept of easy death was also influenced by Confucianism. A sense of duty, moral purity and self-sacrifice were raised to an unattainable height. Samurai were taught from childhood to sacrifice everything for the sake of their master or commander. Therefore, death in the name of fulfillment of duty was considered real life.

The dogmas of Buddhism and Confucianism were well adapted to the professional interests of the samurai. And the psychology and ethics of the samurai further strengthened the glorification of death, self-sacrifice and gave death a halo of glory. All this was closely connected with the cult of death and the rite of hara-kiri.

Buddhist dogmas about life also left their imprint on the attitude towards death. According to them, life is endless, and death is only a link in the constant rebirth into a new life. The death of a samurai, according to Buddhism, did not mean the end of his existence in future lives. Therefore, many samurai, dying on the battlefield, read Buddhist prayers with a smile on their faces. These dogmas also influenced the formation of the etiquette of death, which every samurai had to know and observe.

The religious trend of Zen spread very widely to the life of the samurai, it shaped not only their religious beliefs, but also their behavior. The foundations of Zen teachings were laid down in Bushido, the code of morality of the samurai.

Along with the teachings of Zen, samurai also believed in some Buddhist gods. The goddess of mercy and compassion Kannon (Avalokiteshvara) and the deity Marisiten (Marichi) patronizing warriors were very popular with them.

Among the samurai, before the start of the war, it was common to put a small image of the goddess Kannon into their helmet. And before the start of a battle or duel, the samurai asked the deity Marishiten for help and patronage.

In parallel with Zen Buddhism, samurai believed in the ancient Japanese cult of Shinto. According to this religion, samurai honored their ancestors, nature, local deities and worshiped the souls of warriors killed in battle. One of the main Shinto shrines was the holy sword. The sword was considered a symbol of the samurai and the soul of a warrior.

Along with the Buddhist deities, the samurai also revered the Shintai god of war, Hachiman, whose prototype was the deified emperor of Japan, Ojin. Like the Buddhist goddess Kannon, the samurai also, before the start of the war, turned to the god Hachiman, asked him for support in the upcoming war and took oaths.

The third major religion of the samurai was Confucianism. It was more ideological than religious in nature, in addition to religious moments included ethical ones. Confucianism in Japan adapted to local Buddhism and Shintoism and confirmed such views as: obedience, fidelity to duty, obedience to one's master, moral perfection, strict observance of the laws of the family, society and state.

The fusion of Buddhism, Shinto and Confucianism had a strong impact on the spiritual life of the samurai. It has become commonplace for samurai to simultaneously pray and ask for help from Buddhist and Shinto gods and at the same time observe the moral and ethical standards of Confucianism. Over time, these three currents were closely intertwined in the religious life of the samurai and began to be perceived as one.

See also

-

Sawayama Castle

During the Kamakura period, Sabo Tokitsuna, the sixth son of Sasaki Sadatsuna, built a fort on Mount Sawayama. This fort occupied a strategically important position because it allowed control over traffic along the important Tōsandō route, which was later known as Nakasendō. This road connected the capital, Kyoto, with the eastern regions of the country. Due to its location, the fortification held great military importance, and during periods of civil war it repeatedly became the site of fierce battles.

-

Nadzima Castle

It is believed that the first structures on this site were built by Tachibana Akitoshi (?-1568), head of the Tachibana clan, a branch family of the Ōtomo clan, as auxiliary fortifications for Tachibanayama Castle. In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi established control over the island of Kyushu and granted Chikuzen Province to Kobayakawa Takakage, one of the leading vassals of the Mori clan. Takakage began construction of a new castle on the site of the existing fortifications in 1588. The exact date of completion is unknown, but by the time the invasion of Korea began in 1592, the castle had already been finished, as records note that Toyotomi Hideyoshi stayed there overnight on his way to Hizen Nagoya Castle, which served as the headquarters of the invasion forces.

-

Kubota Castle

The founder of the castle is considered to be Satake Yoshinobu (1570–1633). Yoshinobu was one of the six great generals of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. During the Odawara Campaign of 1590, he took part in the siege of Oshi Castle under the command of Ishida Mitsunari, with whom Yoshinobu developed a good relationship.

-

Kavanhoe Castle

Kawanoe Castle is located on the small Wasi-yama hill near the port area of the Kawanoe district in the city of Shikokuchuo, occupying a central position along the northern coast of Shikoku Island. Kawanoe was also known as Butsuden Castle. The term “butsuden” in Japan refers to temple halls, and for this reason it is believed that a Buddhist temple once stood on the site before the castle was built. Due to its location at the junction of four provinces on Shikoku Island, Kawanoe held significant strategic importance and was repeatedly targeted by rival forces seeking military control over the region.

-

Yokote Castle

The founder of the castle is considered to be the Onodera clan. The Onodera were originally a minor clan from Shimotsuke Province and served Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), the founder of the first shogunate. The Onodera distinguished themselves in battle against the Fujiwara clan of the Ōshū branch and were rewarded with lands around Yokote. Around the 14th century, the Onodera moved to Yokote as their permanent residence. Their original stronghold was Numadate Castle, but after a series of clashes with the powerful Nambu clan, they relocated their base to the site of present-day Yokote Castle. It was likely during this time that the first fortifications appeared at the castle.

-

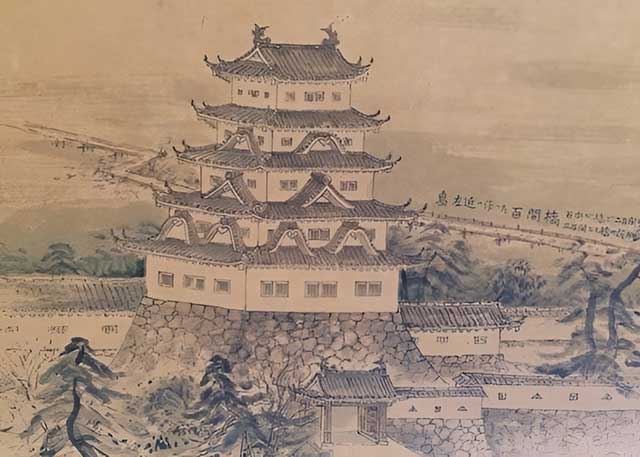

Wakayama Castle

Wakayama Castle was built in 1585, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered his uterine brother, Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hidenaga, to construct a castle on the site of the recently captured Ota Castle. The purpose of this construction was to secure control over the likewise newly conquered Province of Kii. Following an already established tradition, Hidenaga entrusted the project to his castle-building expert, Todo Takatora. Takatora carefully inspected the future castle site, personally drew up several designs, created a model of the planned castle, and took part in the work of laying out the grounds (nawabari). For the construction he brought in more than 10,000 workers and completed the large-scale project within a single year, which was considered extremely fast by the standards of the time.

Toyama Castle

Toyama Castle is located almost in the very center of the former province of Etchū and is surrounded by a wide plain with a large number of rivers. The very first castle on the banks of the Jinzu River was built in 1543 by Jimbo Nagamoto. The Jimbo clan were vassals of the Hatakeyama clan and governed the western part of Etchū Province. The eastern part of the province belonged to their rivals, the Shiina clan, who were also Hatakeyama vassals. Beginning in the 15th century, the influence of the ancient Hatakeyama clan gradually weakened, and as a result, the Jimbo and the Shiina fought constant wars for control of the province. Meanwhile, the forces of the Ikkō-ikki movement periodically intervened, helping first one side and then the other.

Takada Castle

During the Sengoku period, the lands where Takada Castle would later be built were part of Echigo Province and were controlled by the Uesugi clan.