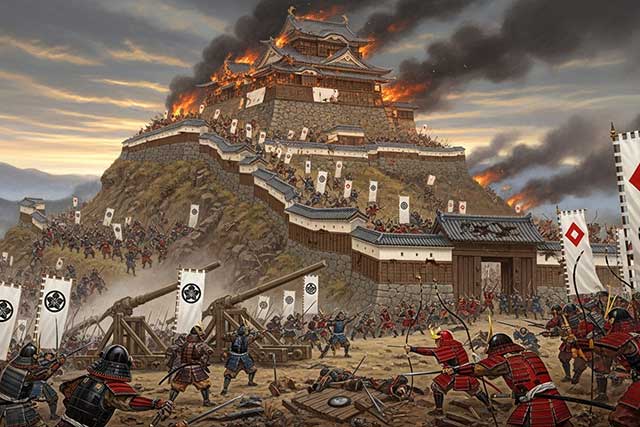

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

Jinju belonged to the type of fortified cities known as ypsons and was considered one of the most powerful fortresses in the southern part of the Korean peninsula. The southern side of the castle faced the Nam River, whose banks had a steep slope. A wide and high stone wall was erected around the city, and the passages in it were protected by gates with pavilions. Watchtowers stood around the perimeter, and on the north side, along the walls, a moat was dug, filled with water from the river. The garrison was armed with a number of cannons and mortars.

The capture of Jinju would deprive the Korean partisans of an important base of support and open the way for the Japanese army to the southwest, to the rich province of Chollado.

The first siege of 1592

In 1592, the Japanese made their first attempt to capture the fortress. Siege towers and ladders were used in the assault. As in other battles of the Korean campaign, the Japanese relied mainly on arquebus fire. The Koreans could only respond with arrows from their archers and shots from a few cannons, but it is known that during the defense of Jinju, the besieged used about 170 guns similar in characteristics to the Japanese ones. The first siege ended in defeat for the Japanese—they had to retreat and abandon their positions.

Preparation for the second siege

The Japanese troops received significant reinforcements and returned to the walls of Jinju in July 1593, beginning a second siege with an army of about 90,000 men. Almost all the main commanders of the invading forces took part in the operation: Konishi Yukinaga, Kato Kiyomasa, Kuroda Nagamasa, Kobayakawa Takakage, Ukita Hideie, Mori Hidemoto, and Kikkawa Hiroie.

The fortress garrison numbered about four thousand soldiers under the command of General Kim Jeong-il. In addition, a large number of civilians, including artisans and peasants, participated in the defense, helping the soldiers in the fortifications.

Konishi, Kato, and Ukita's troops were positioned directly under the northern walls of the castle. Kikkawa's soldiers stood on the opposite bank of the river opposite the fortress, while the remaining units formed an outer circle of siege to prevent attempts to break the blockade by Korean partisans or Chinese reinforcements.

The beginning of the siege and the first attacks

In preparation for the assault, the Japanese prepared a large number of bamboo bundles, called taketaba, which were used as cover. In addition, wooden portable shields, called tate, and wheeled shields, called kurumadate, were made.

First, the besiegers destroyed the dams that held water in the moat beneath the castle walls. They managed to drain the moat, after which they filled it with stones, earth, and branches, creating a path for the attack.

The Japanese went on the attack under the cover of shields and bamboo bundles, but the Koreans met them with a hail of bullets, cannonballs, and flaming arrows. They managed to set fire to and destroy most of the portable fortifications. Having lost many men, the Japanese were forced to retreat.

Construction of siege engines and new attacks

The Japanese spent the next two days building new siege engines. They erected stationary and mobile towers from which they could observe and fire, as well as wooden “bridges to the sky” and assault ladders.

However, the new assault was again unsuccessful. The Koreans managed to destroy the siege towers with artillery fire and also inflicted serious damage on the enemy with the help of unusual anti-infantry devices called “wolf's mouths.”

These devices were wide wooden shields studded with metal blades. They were lowered along ropes along the walls to cut down enemies climbing the walls. After that, the structures were pulled back up on winches and could be reused. Prior to the Korean campaign, the Japanese had never encountered this type of weapon anywhere else.

During one of the assaults, a Korean militia army known as the “army of justice” approached the castle, but it was defeated by the Japanese rearguard.

The final attacks and the fall of the fortress

A few days later, Ukita Hideie sent General Kim Jeong-il a letter proposing surrender, but he refused. The Japanese then decided to use covered carts—kikkosha—to shake the foundation stones of the wall and collapse part of the fortification.

The moat at the site of the attack was covered with grass, creating a flat surface over which the carts could pass. However, the Koreans began throwing burning torches from above and set fire to both the grass and the kikkyo themselves. Despite the partial success of the undermining, the Japanese were again forced to retreat.

Then, Kato Kiyomasa suggested covering the carts with wet ox hides to protect them from the fire. With their improved machines, the Japanese launched a decisive assault, attacking the northeast corner of the fortress.

The heavy rain that began that day played into their hands: the Koreans' fire weakened and the ground softened, allowing the carts to get closer. The Japanese managed to knock down part of the wall, and samurai rushed into the breach, literally pushing each other aside in their eagerness to be the first. The castle fell almost instantly. There was no resistance left inside the fortress. A mass slaughter began.

According to Japanese sources, twenty thousand people were taken prisoner as a result of the siege, while according to Korean sources, about sixty thousand people were killed, which is practically the entire population of the city.

Thus ended the second siege of Jinju, one of the bloodiest and most tragic events of the Korean campaigns of the late 16th century.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.

-

The Third Siege of Takatenjin Castle

The history of the castle prior to the conflict between the Tokugawa and Takeda clans is rather unclear. According to one version, the castle was built in 1416, when Imagawa Sadayoshi (1325–1420) was governor of Suruga Province and half of Totomi Province. Allegedly, it was he who ordered Imagawa Norimasa (1364–1433) to build this fortification. However, no reliable evidence has been found to support this. Another version is considered more plausible, according to which the castle was built during the conquest of Totomi Province at the end of the 15th century by Imagawa Ujitsuna (1473–1526) and his general Ise Shinkuro (Hojo Soon). In this case, another of Ujitsuna's generals, Kusima Masashige (1492–1521), is considered responsible for the construction.