The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

The Honda clan was entrusted with supervising the demolition of the fortifications. They rushed and pressured the samurai so much that within a week, the outer wall of the fortifications had been completely thrown into the outer moat, which thus ceased to exist.

The commanders in Osaka naturally protested, and their indignation intensified when Honda's “diggers” began work on the second moat. Honda apologized, explaining that his officers had probably misunderstood the orders. In the presence of representatives from Osaka, he personally ordered the work to be stopped. However, as soon as the envoys left, the filling resumed with redoubled force.

Then, outraged, Yodogimi went to Kyoto to protest to Honda's elder, Masanobu. He assured her that he would see to it that the destruction was stopped. Unfortunately, he said, he had a bad cold, but he would definitely contact his nephew as soon as he recovered. True to his word, Honda Masanobu soon arrived in Osaka, scolded his nephew for his “stupidity,” and told Yodogimi that digging a second moat would now require ten times more work than had been spent filling it in.

In addition, he added, peace had been concluded, and the moat was no longer needed. Twenty-six days after work began, the second moat was also completely filled in. Osaka's fortifications were left with only one moat and one wall. Unsurprisingly, for the Japanese, the “winter campaign at Osaka” became a symbol of foolish pacifism.

The start of the summer campaign

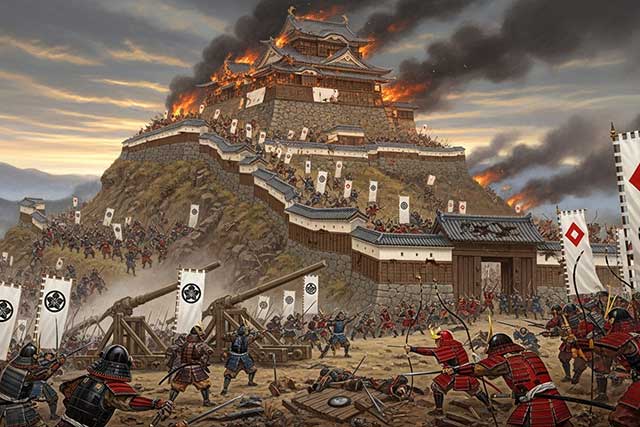

Three months later, Ieyasu attacked Osaka Castle again. In this “summer campaign,” he intended to crush the enemy “once and for all, decisively and effectively.”

The only thing he needed was a pretext to start the war. Reports that Hideyori was rebuilding the second moat served as a reason to accuse him of violating the treaty. Rumors spread throughout Kyoto about ronin allegedly planning to plunder the capital made Ieyasu almost a savior in the eyes of the people.

Hideyori did indeed manage to rebuild significant sections of the second moat and reinforce them with a palisade. More than 120,000 people gathered under his banners, decorated with his father's “golden bucket” — 60,000 more than in the winter campaign. Among them were again many Christians; six large banners were decorated with crosses, and foreign priests were in the fortress. Tokugawa's forces were estimated to number as many as a quarter of a million.

First clashes

The Osaka troops were the first to attack. On May 28, Ono Harufusa invaded Yamato Province with 2,000 soldiers, burning everything in his path, and reached Nara. On May 30, he turned south to block the advance of Asano's army and burned the city of Sakai.

The Osaka garrison's spirits were lifted once again. They had been humiliated in the winter, but they were not defeated. Now, if they could defeat Tokugawa's separate divisions before their main forces arrived, they could avoid a siege of their weakened castle. They almost succeeded.

On June 1, the army marched out to block the roads from Nara. However, fog misled most of the troops, and only 2,400 men under the command of Goto Mototsugu clashed with the numerically superior enemy and were crushed. Meanwhile, Yosokabe and Kimura tried to hold back Todo and Ii, but were pushed back. The garrison retreated to the castle, or rather, to its ruins.

On June 2, 1615, a military council decided to meet the Tokugawa army in open battle south of the former outer moat.

The Battle of Tennōji

This battle, known as the Battle of Tennōji, was the last major clash between samurai armies in Japanese history—the last battle of the samurai.

The defense plan was ambitious: Sanada, Ono, and other commanders were to attack the enemy's front, while Akashi Morishige was to flank them from the rear. When Akashi's attack began, Hideyori himself was to lead a sortie with his father's “golden bucket.”

On the morning of June 3, Tokugawa's troops stretched from the Hirano River to the sea. Maeda Toshitsune stood on the right, Todo on the left, followed by Ii Naotaka with the “Red Devils.” At the vanguard was Tadamoto, Honda's son; the left flank was held by Date Masamune, and the rear by Asano Nagaakira. Hidetada, Ieyasu's son, was appointed commander-in-chief.

The Osaka forces, numbering about 54,000 men, took up positions behind Tennoji under the command of Sanada Yukimura and Mori Katsunaga.

It was a clear summer day. The armies stared intently at each other—the last battle of their era was ahead. Suddenly, Mori Katsunaga's impatient ronin opened fire with their arquebuses. Sanada tried to stop the premature battle, but to no avail: the fighting broke out.

Mori led his men into the attack, broke through the front ranks of the Tokugawa and burst into their center. Sanada, realizing that retreat was impossible, sent a messenger to Hideyori demanding that he advance immediately. However, the sudden movement of Asano's samurai along the sea aroused suspicion of treason — cries of “treason!” rang out through the ranks.

The death of Sanada Yukimura

The Etzen soldiers retreated in disorder. Ieyasu, alarmed, entered the battle himself to raise the spirits of his men. According to legend, he was wounded by a spear near his kidney and was even ready to commit seppuku.

The situation was saved by the young Honda, who led his troops against Sanada and pushed him back to Tennōji. Exhausted, Sanada Yukimura sat down on a folding chair. The samurai Nishiō Nijemon approached, and Sanada, having no strength left to fight, simply introduced himself and took off his helmet. Thus fell the bravest of the brave.

His death inspired the Eastern Army. Suspicions of Asano's betrayal were dispelled: his actions turned out to be nothing more than an unsuccessful attempt to send reinforcements. Hidetada separated Ii and Todo from the right wing, sending them to help the main forces. Todo's soldiers experienced the horrors of war when an underground mine exploded beneath them.

Meanwhile, Oda Harunaga threw his forces against Hidetada, who struggled to restore order with the help of Kato Yoshiaki and Honda Masanobu. Maeda did not move immediately, as his soldiers were having lunch, for which he was almost suspected of treason.

The end of the Toyotomi family

The Osaka troops were already faltering. Ii Naotaka rushed to their aid, but his standard-bearers were shot. Confusion broke out in the ranks. Hidetada almost found himself in the thick of battle, but the officers managed to pull him back. Meanwhile, Maeda, having finished his lunch, attacked Ono, and Date Masamune shot his warrior, suspected of treason.

If Osaka's attack had gone according to plan, the outcome could have been different. But Akashi was intercepted, and Hideyori was late. When he appeared at the gate, it was all over: the forces of the Eastern Army were pushing the garrison back to the walls. The events that followed were bloody and chaotic. The Eastern Army stormed the castle. Mizuno Katsushige planted his standard at the Sakura Gate. By evening, the castle had fallen.

Hideyori retreated to the citadel. Ieyasu ordered Ii Naotaka to “guard” him, but Naotaka understood this as an order to destroy him: the artillery bombardment began. Flames engulfed the fortress. It is said that the first fire was started by Hideyori's cook.

By five o'clock in the evening, the castle was in Ieyasu's hands. Hideyori and Yodo-dono, surrounded by fire, committed suicide. The citadel of Hideyoshi's great castle became the funeral pyre of the Toyotomi family. When the ashes cooled, retribution came.

To ensure that no uprising would ever threaten the Tokugawa's power, Hideyori's eight-year-old son was beheaded. He was the last of the Toyotomi clan. The same fate befell Chosokabe Moritaka. The heads of the fallen ronin were displayed along the road from Kyoto to Fushimi as a grim reminder of the end of the samurai era.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.

-

The Third Siege of Takatenjin Castle

The history of the castle prior to the conflict between the Tokugawa and Takeda clans is rather unclear. According to one version, the castle was built in 1416, when Imagawa Sadayoshi (1325–1420) was governor of Suruga Province and half of Totomi Province. Allegedly, it was he who ordered Imagawa Norimasa (1364–1433) to build this fortification. However, no reliable evidence has been found to support this. Another version is considered more plausible, according to which the castle was built during the conquest of Totomi Province at the end of the 15th century by Imagawa Ujitsuna (1473–1526) and his general Ise Shinkuro (Hojo Soon). In this case, another of Ujitsuna's generals, Kusima Masashige (1492–1521), is considered responsible for the construction.