The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

The Shimabara Peninsula on the island of Kyushu was one of the historical centers of Catholic Christianity in Japan since the mid-16th century. Under the daimyo Konishi Yukinaga, who was himself a Christian, Jesuit missions were active in the area. There was a monastery, a seminary, and a priests' house in Shimabara, and the number of followers reached 70,000.

After Toyotomi Hideyoshi's 1587 edicts expelling Jesuit missionaries from the country, some Christian priests secretly hid in Shimabara and contributed to the growth of the Christian community. Yukinaga was executed in 1600 after his defeat in the Battle of Sekigahara, and the newly formed principality of Shimabara went to the Christian daimyo Arima Harunobu, who continued to support Christianity in his domain.

From 1596, persecution of Christians began in Japan, which became particularly brutal after Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu came to power in 1623. The repression on the Shimabara Peninsula and the nearby Amakusa Islands was led by the central government's appointees, Matsukura Shigemasa, the new lord of Shimabara, and Terazawa Katataka, the new daimyo of the Karatsu domain.

Shigemasa's son and successor, Matsukura Katsuie, who took over the domain in 1630, was particularly cruel. One of his favorite tortures was to put a straw cloak on a bound peasant and then set him on fire. Through threats, torture, and executions, Matsukura and Terazawa achieved the formal renunciation of Christianity by the majority of the population by 1633.

The deterioration of the people's situation

The anti-Christian repression coincided with devastating typhoons and a prolonged drought (1633–1637) that caused famine. Despite this, taxes were not reduced, and food was seized by force.

In 1636, an order came from the capital for Shimabara and Karatsu to participate in repair work on the shoguns' residence in Edo, which placed an even greater burden on the region's peasants.

The beginning of the uprising

The uprising began on December 17, 1637, in the Matsukura domain with the murder of a local tax official. It quickly grew into a peasant revolt led by several ronin, and then spread to the Amakusa Islands. According to some estimates, the number of rebels reached 37,000.

Soon, the charismatic 16-year-old samurai Amakusa Shiro took the lead in the rebellion. The son of a former vassal of the Konishi clan, the Christian Masuda Jimbay, he was also baptized and took the Christian name Jerome.

The rebels saw in him the “Fourth Son of Heaven” predicted by the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier, who, according to prophecy, was to lead the Christianization of Japan. Legends were told about Shiro: that birds flew to him and landed on his hand, that he could walk on water and breathe fire from his mouth. His followers extolled him as a messenger from heaven, although he himself never claimed to be divine.

Some researchers believe that the rebellion was the result of a conspiracy by former vassals of the executed daimyo Konishi Yukinaga, chief among them Masuda Jimbay, and that rumors of the coming of the Messiah were deliberately spread by Catholic priests. However, this does not negate the root cause of the uprising: the plight of the peasants and the brutal religious persecution in the region.

The first battles

The rebels laid siege to the Terazawa clan's castles of Tomioka and Hondo in Amakusa. After several assaults, the castles were close to surrender, but government troops assembled from the armies of several principalities on the island of Kyushu arrived.

The rebels lifted the siege, boarded boats, and crossed over to the Shimabara Peninsula, where at the end of January 1638, they laid siege to the castle of the same name, which belonged to Matsukura Katsuie. They managed to seize an arsenal of various weapons, including firearms, by looting one of the warehouses in the castle town, but the fort itself held out. Under threat of another attack, the rebels retreated to Hara Castle.

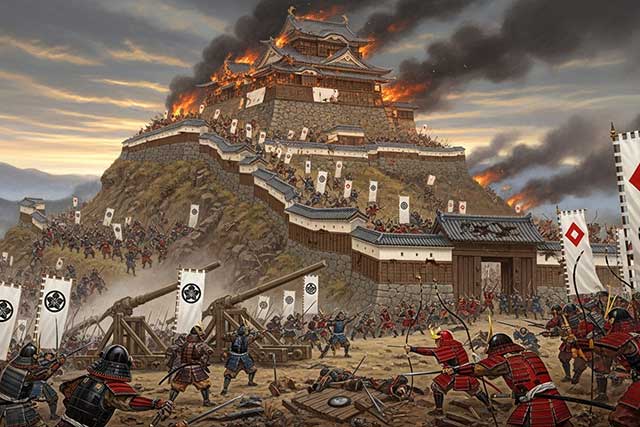

The Siege of Hara Castle

Hara Castle had previously belonged to the Arima clan, but was later abandoned. Only its stone walls and moats remained. Siro's army built palisades and other fortifications on top of the remaining walls.

Soon, flags with the character “ju” (similar to a cross and used on the banners of Christian daimyo) fluttered above the castle walls, and wooden crosses appeared — the rebels openly declared their religious affiliation.

By this time, news of the rebellion had reached the central government, and Itakura Shigemasa, who led an army of 50,000 local princes, was sent by the shogunate to pacify the rebels. He began a siege, but three attempts at a direct assault were repelled.

There is evidence that Shigemasa tried to send in saboteurs and dig tunnels under the walls, but without success. Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, dissatisfied with the delay in suppressing the “insignificant peasant rebellion,” sent one of his highest officials, Matsudaira Nobutsuna, to replace Shigemasa.

In an attempt to justify his failures, Shigemasa led a fourth assault, but was killed, and the attack was again unsuccessful.

Reasons for the rebels' resilience

The question arises: how could untrained peasants resist the vastly superior forces of professional samurai?

First, the professionalism of the shogunate's warriors had declined significantly compared to the veterans of the Sengoku Jidai battles. The last serious military conflict had ended 23 years earlier, and the new generation of samurai had become accustomed to peaceful life.

Second, among the rebels were ronin samurai who were familiar with military affairs, while the peasants, who made up the majority, had received minimal training in the use of weapons.

Interestingly, Prince Shimabara Matsukura Shigemasa had previously proposed an ambitious plan to the shogunate to attack the Spanish missionaries' base on the island of Luzon (Philippines). Having received unofficial approval, he borrowed money from merchants in Sakai, Hirato, and Nagasaki, bought arquebuses and gunpowder, and began training his peasants in shooting, intending to include them in the campaign.

The shogunate later rejected this idea, and his successor, Matsukura Katsuie, had to repay the debts to creditors, for which he raised taxes. Ironically, the peasants trained by his father fired at his soldiers with weapons purchased by Shigemasa himself.

Blockade and Dutch involvement

With the arrival of reinforcements along with Matsudaira Nobutsuna, the besiegers' forces grew to 125,000 men. Nobutsuna decided to change tactics and switched to a blockade.

He requested support from the Dutch, who supplied cannons and gunpowder. The head of the Dutch mission also agreed to provide the ship De Ruyp for shelling the fortress.

The castle was bombarded simultaneously from land and sea; about 426 cannonballs were fired in 15 days. However, the bombardment did not produce any noticeable results. Moreover, the Dutch themselves suffered losses — the besieged managed to shoot two sailors on the De Ruyp with their guns.

The last days of the defense

An arrow was shot from the castle to the besiegers' camp with a note in which the rebels sarcastically asked whether the shogunate had run out of brave men, since they were relying on the help of foreigners against a handful of peasants.

Perhaps this message was the reason for the change in tactics, or perhaps the besiegers simply recognized that the bombardment was ineffective, but on February 3, the rebels launched a surprise counterattack, killing about two thousand shogunate soldiers. However, this was their only success. Gradually, food supplies began to run out.

On April 4, the defenders attempted a sortie to replenish their supplies, but were defeated. Several rebels were captured and, under torture, revealed that there was famine and a shortage of gunpowder in the castle. According to other sources, the information was passed on by a traitor.

On April 12, the shogunate troops attacked the weakened defenders and captured the outer ring of fortifications. The rebels fought fiercely, but the castle did not fall completely until April 15. The losses of the besiegers reached, according to various estimates, about 10,000 people.

The end of the rebellion and its consequences

After the fall of Hara Castle, the shogunate executed about 30,000 people — all the surviving rebels and even their sympathizers. The severed heads of Amakusa Shiro and other leaders of the rebellion were put on public display in Nagasaki. Hara Castle was burned to the ground and then buried under earth along with the bodies of the dead. Matsukura Katsuie was put on trial and, when the details of his cruel treatment of the peasants came to light, he was beheaded.

The shogunate, suspecting European Catholics of inciting the rebellion, finally expelled the Portuguese from the country. The period of sakoku isolation entered its most severe phase. Christianity was completely banned and survived only in underground communities. With the exception of minor local disturbances, the Shimabara Rebellion was the last military campaign of the Edo period until the beginning of the Bakumatsu period in the 19th century.

See also

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.

-

The Third Siege of Takatenjin Castle

The history of the castle prior to the conflict between the Tokugawa and Takeda clans is rather unclear. According to one version, the castle was built in 1416, when Imagawa Sadayoshi (1325–1420) was governor of Suruga Province and half of Totomi Province. Allegedly, it was he who ordered Imagawa Norimasa (1364–1433) to build this fortification. However, no reliable evidence has been found to support this. Another version is considered more plausible, according to which the castle was built during the conquest of Totomi Province at the end of the 15th century by Imagawa Ujitsuna (1473–1526) and his general Ise Shinkuro (Hojo Soon). In this case, another of Ujitsuna's generals, Kusima Masashige (1492–1521), is considered responsible for the construction.