Fujiwara no Hirotsugu was the son of Fujiwara no Umakai, one of the most important court officials of the Nara period. By 740, the Fujiwara clan had held the reins of government for several decades. However, in 735–737, Japan suffered a severe trial: the country was hit by a devastating smallpox epidemic. It coincided with a series of crop failures, and together, disease and famine claimed the lives of about 40% of the population of the Japanese islands. The consequences were particularly tragic for the aristocracy. The mortality rate among the court nobility exceeded that among the common people. All four Fujiwara brothers, who held the most important positions at court — Umakai, Maro, Mutimaro, and Fusasaki — died.

This was exploited by the clan's worst enemy, Tatibana no Moroe (684–757). Just one year after the brothers' deaths, he managed to seize power at court and began to exert enormous influence over the emperor.

Fujiwara no Hirotsugu was one of the victims of these court intrigues. In 738, he was appointed to the high and lucrative post of governor of Yamato Province, but a year later, due to Moroe's intrigues, he was removed from office and sent to the provincial town of Dazaifu in northern Kyushu. Humiliated and embittered, in 740 Hirotsugu sent an official protest to the court, demanding punishment for those responsible for his downfall. He considered Tachibana no Moroe to be his main enemy, as well as those close to the court — the dignitary Kibi no Makibi and the monk Gembo, who wielded considerable influence. But at the court, which was completely subordinate to Moroe, this appeal was perceived as a rebellion. Hirotsugu had no way back. Four days after receiving the message, on the 3rd day of the 9th month of 740, he raised a rebellion.

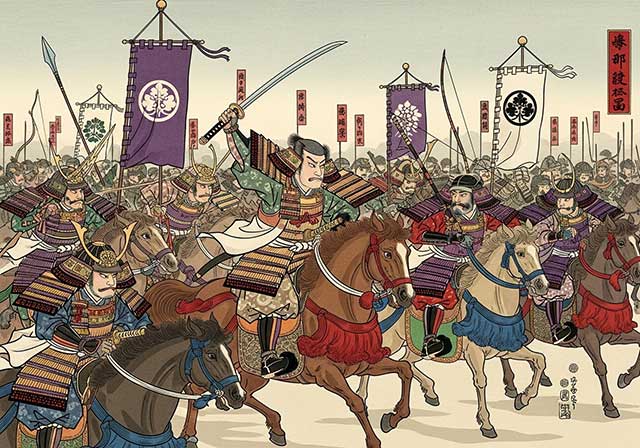

The court responded by sending an expeditionary army of 17,000 soldiers. Ono no Azumabito, a court aristocrat, was appointed supreme commander (taishogun, “great commander”). The appointment of a civilian official to the post of commander-in-chief was no accident: the imperial court had always feared the excessive strengthening of the military and therefore preferred to keep command in the hands of the aristocracy.

Government troops gathered in both eastern and western Japan, with the exception of Kyushu itself. At the same time, Hirotsugu, taking advantage of his position as a provincial official, began to recruit his own army on the island. According to the Shoku Nihongi chronicle, he managed to gather between 12,000 and 15,000 soldiers. He divided these forces into three armies: the northern army was commanded by Hirotsugu himself, the central army by his subordinate Komaro, and the southern army by another associate named Tsunae. Hirotsugu's plan was simple: to concentrate all his troops in northeastern Kyushu and take up defensive positions at the narrow strait separating Kyushu and Honshu. There, he hoped to drive the imperial army into the sea while it was still attempting to land.

Hirotsugu did indeed take up fortified positions in Miyako County in Bizen Province and waited for the allied armies to approach. But events did not go as he had expected. One army was late, and the other did not arrive at all. The government troops took advantage of this: they managed to land without much difficulty and put Hirotsugu's forces to flight. This happened on the 24th day of the 9th month of 740. Two of his commanders were killed in battle: the chief of fortifications in Miyako and the commander of Itabitsu Fort. Hirotsugu himself, wounded by two arrows, managed to escape with the remnants of his defeated army.

Meanwhile, the imperial court reinforced the expeditionary army. On the 21st and 22nd of the 9th month, an additional 4,000 soldiers were sent, among whom were 40 elite fighters — jōhei, specially noted in the chronicle Shōkoku Nihongi. On the 25th, four district chiefs defected to the government and attacked the remnants of Hirotsugu's army with 500 horsemen. One by one, his comrades began to retreat and betray him.

The final defeat came in the decisive battle on the Itabitsu River. Hirotsugu's army completely collapsed, and he himself fled again. But on the 23rd day of the 10th month, Hirotsugu was captured, and a week later, he was beheaded.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.