Upon Toyotomi Hideyoshi's death in 1598, Japan entered a period of governance by the Council of Five Elders, with Tokugawa Ieyasu wielding the most influence. Following his victory over Ishida Mitsunari in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Ieyasu effectively seized control of Japan and disbanded the Council. In 1603, the Tokugawa shogunate was established in Edo, with Hideyoshi's son, Toyotomi Hideyori, and his mother, Yodo-dono, permitted to reside at Osaka Castle. Hideyori was granted a significant fief valued at 657,400 koku but remained confined to the castle for several years. As a means of control, it was arranged for Hideyori to marry Senhime, the daughter of Hidetada, in 1603, who had ties to both clans. Ieyasu aimed to establish a strong and stable regime under his clan's rule, with only the Toyotomi, led by Hideyori and influenced by Yodo-dono, posing a challenge to his ambitions.

In 1611, Hideyori departed Osaka and met with Ieyasu at Nijo Castle for two hours, surprising Ieyasu with his demeanor, contrary to the belief propagated by Katagiri Katsumoto, Hideyori's guardian, that the boy was ineffectual. In 1614, the Toyotomi clan reconstructed Osaka Castle and sponsored the rebuilding of Hoko-ji in Kyoto, including the casting of a large bronze bell inscribed with wishes for peace and prosperity. However, the shogunate interpreted the inscriptions as curses against Ieyasu and as a sign of treachery. Tensions heightened as Toyotomi started gathering a sizable contingent of ronin and adversaries of the shogunate in Osaka, even after Ieyasu relinquished the title of Shogun to his son in 1605.

After the Hoko-ji Temple Bell Incident, Yodo-dono dispatched envoys to negotiate with Ieyasu, but he exploited the divisions within the Toyotomi family to further his own agenda. Despite efforts to mediate, Ieyasu took a hostile stance against Yodo-dono and Hideyori, exacerbated by reports of ronin gathering in Osaka. Suspecting betrayal, Yodo-dono expelled Katagiri Katsumoto and others accused of treason, eliminating any chance of reconciliation with the shogunate. This marked the beginning of the siege of Osaka.

The first battle

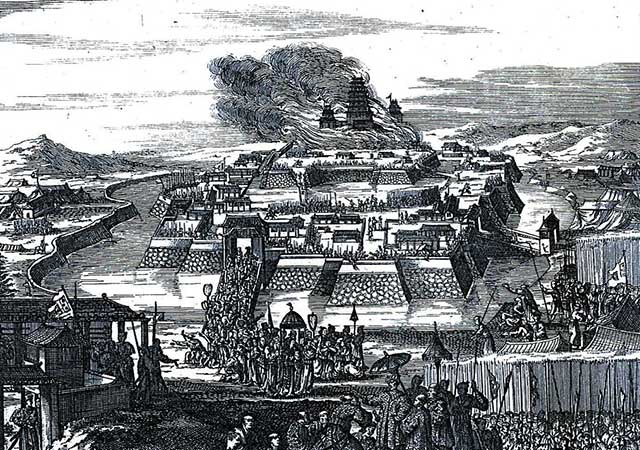

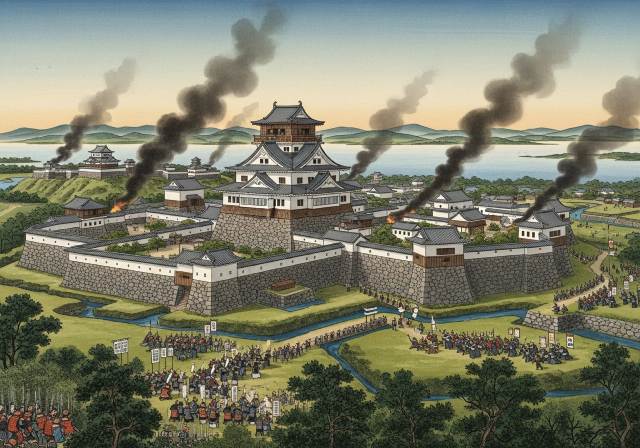

In November of 1614, Tokugawa Ieyasu made the decision to prevent further expansion of this force, leading 164,000 men to Osaka. (This count excludes the troops of Shimazu Tadatsune, an ally of the Toyotomi cause who did not send troops to Osaka.) The siege commenced on 19 November when Ieyasu crossed the Kizu River with 3,000 men, demolishing the fort there. A week later, he launched an attack on the village of Imafuku with 1,500 men, overpowering a defending force of 600 with the help of a squad armed with arquebuses. Afterward, additional minor forts and villages were singled out before the siege of Osaka Castle began on December 4th.

The Sanada-maru, an earthwork barbican defended by Sanada Yukimura and 7,000 men on behalf of the Toyotomi, repeatedly repelled the Shogun's armies. Sanada and his men launched numerous attacks against the siege lines, breaching them three times. Ieyasu subsequently resorted to artillery, employing 17 cannons imported from Portugal and 300 domestically produced wrought iron cannons, while also initiating tunneling operations beneath the walls.

Recognizing the formidable defenses, Ieyasu initiated a limited bombing campaign on January 8, 1615. For three consecutive days, his forces bombarded the fortress at night and dawn, while miners tunneled under the walls and arrows with surrender messages were launched inward. By day 15, with no response from the besieged, Ieyasu intensified the bombardment to weaken the defenders' morale. However, the castle's stone bases remained impervious to artillery, and its structure remained largely intact.

Attempting to sway Sanada Yukimura, who harbored a strong animosity towards him, Ieyasu offered bribes, which were rejected and made public. Subsequently, Ieyasu tried to subvert the castle's defenses by bribing another commander, Nanjo Tadashige, to open the gates. When this treachery was discovered and Nanjo was executed, Ieyasu shifted tactics, targeting Yodo-dono's quarters with cannon fire.

During a night attack on the 16th, Ban Naotsugu led a successful assault on the troops of Hachisuka Yoshishige, followed by continued bombardment the next day, coinciding with the anniversary of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's death. Ieyasu believed Hideyori would be in the temple dedicated to his father, directing fire toward that location. The projectile narrowly missed Hideyori's head, striking a pillar instead, instilling fear in Yodo-dono and prompting her to seek terms with the shogunate.

On January 17, Ieyasu sent envoys to negotiate surrender terms with Ohatsu, Yodo-dono's younger sister. Despite initial resistance, Yodo-dono eventually accepted the terms, and hostages were exchanged, culminating in a solemn oath from Hideyori and Yodo-dono to abide by the conditions laid out by Ieyasu. Subsequently, the exterior defenses of the castle were dismantled, leading to Ieyasu's departure from Osaka, where he declared an end to the conflict.

However, tensions persisted, and reports of Ieyasu's true intentions prompted Hideyori to reinforce the fortress and seek support from ronin. Hideyori and his generals decided to take the offensive, securing areas surrounding Osaka and planning to seize control of Kyoto to sway the emperor against Ieyasu. As rumors spread, the population of Kyoto fled, and even some members of the shogunate were implicated in alleged plots. Meanwhile, Ieyasu continued his preparations, meeting with his troops in Nagoya before advancing towards Osaka.

The second battle

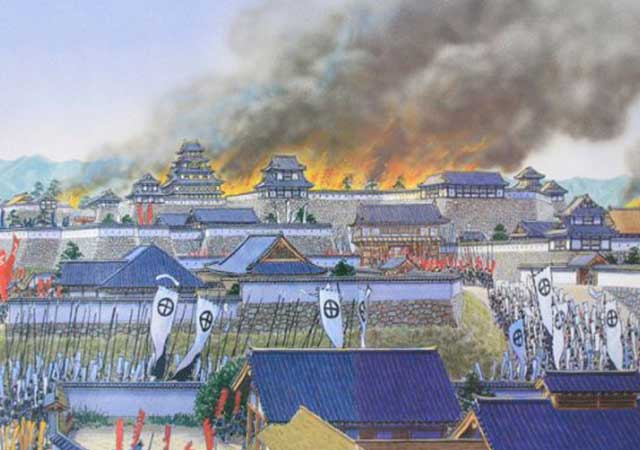

In April 1615, Ieyasu received alarming reports of Toyotomi Hideyori amassing even greater troops than the previous November and attempting to halt the moat's filling. The Toyotomi forces, often referred to as the Western Army, initiated attacks on sections of the Shogun's forces, known as the Eastern Army, near Osaka. On 26 May (Keicho 20, 29th day of 4th month), the Battle of Kashii erupted, with Osaka forces led by Ono Harufusa and Ban Danemon clashing against the troops of Asano Nagaakira, a Shogunate ally. Osaka suffered a defeat, and Ban Danemon met his demise.

On 2 June (Keicho 20, 6th day of 5th month), the Battle of Domyoji unfolded as Osaka forces endeavored to impede the Tokugawa forces advancing from Yamato Province along the Yamato-gawa river. During the battle, two Osaka generals, Goto Matabei and Susukida Kanesuke, fell in combat. Despite the engagement between Osaka forces' commander Sanada Yukimura and Date Masamune's forces, the Osaka forces eventually withdrew towards Osaka Castle, and the Tokugawa forces chose not to pursue them. Concurrently, Chosokabe Morichika and Todo Takatora clashed at Yao, while another skirmish occurred at Wakae, involving Kimura Shigenari and Ii Naotaka. Despite Chosokabe's victory, Kimura Shigenari faced resistance from the left wing of Ii Naotaka's army and ultimately succumbed. The main Tokugawa forces redirected their efforts to support Todo Takatora after Shigenari's demise, prompting Chosokabe to withdraw temporarily.

After the battles.

Toyotomi Kunimatsu, Hideyori's son at the tender age of 8, was apprehended by the shogunate and executed in Kyoto. According to legend, prior to his execution, young Kunimatsu bravely accused Ieyasu of betraying and brutally mistreating the Toyotomi clan. Nāhime, Hideyori's daughter, was spared from the death sentence. Ohatsu and Senhime intervened to rescue Nāhime, adopting her; she later became a nun at Kamakura's Tokei-ji. The shogunate razed Hideyoshi's tomb and Toyokuni Shrine in Kyoto. Chosokabe Morichika met his demise through beheading on May 11. Additionally, there are documented instances of pillaging and widespread sexual violence by Tokugawa forces as the siege came to an end.

The bakufu gained control of 650,000 koku in Osaka and commenced the reconstruction of Osaka Castle. Osaka was designated as a han (feudal domain) and granted to Matsudaira Tadayoshi. However, in 1619, the shogunate replaced Osaka Domain with Osaka Jodai, overseen by a bugyo directly serving the shogunate. Similar to many other major cities in Japan during the Edo period, Osaka remained outside the control of a daimyo's han. Some daimyo, including Naito Nobumasa (Takatsuki Castle, Settsu Province, 20,000 koku) and Mizuno Katsushige (Yamato Koriyama, Yamato Province, 60,000 koku), relocated to Osaka.

Following the castle's fall, the shogunate enacted laws such as ikkoku ichijo (one province, one castle) and Bukeshohatto (Law of Buke), restricting each daimyo to owning only one castle and obliging adherence to castle regulations. Henceforth, permission from the shogunate was mandatory for any castle construction or repair. Many castles were demolished in compliance with this law.

Despite successfully unifying Japan, Ieyasu's health deteriorated. Sustaining injuries during the one-year campaign against the Toyotomi clan and its allies, he faced a shortened lifespan. Roughly a year later, on June 1, 1616, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the last of Japan's great unifiers, passed away at the age of 75, leaving the shogunate to his descendants.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.