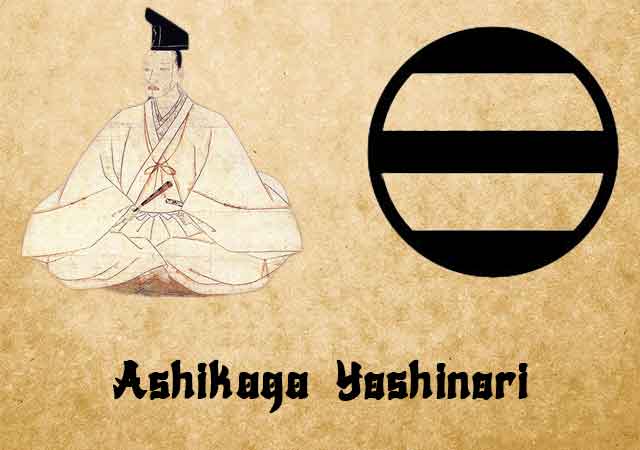

Ashikaga Yoshinori (July 12, 1394 – July 12, 1441) assumed the role of the sixth shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate, governing from 1429 to 1441 during Japan's Muromachi period. Born as the son of the third shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, he was known as Harutora in his youth.

Following the passing of the fifth shogun, Ashikaga Yoshikazu, in 1425, the fourth shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimochi, resumed leadership of the shogunate. Yoshimochi, having no other sons and having not designated a successor before his own demise in 1428, left the future of the shogunate uncertain.

Upon Yoshimochi's passing, Yoshinori, who had embraced monastic life at the age of ten, assumed the role of Sei-i Taishogun. His appointment was orchestrated by the shogunal deputy, Hatakeyama Mitsuie, who, within the sanctum of Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in Kyoto, selected Yoshinori from a pool of potential Ashikaga successors. It was believed that the influence of Hachiman played a role in this auspicious decision.

Yoshinori officially took the mantle of shogun in 1429, a year prior to the Southern Court's surrender. However, his reign was marked by several uprisings, including the Otomo rebellion and the insurrection of rebel monks on Mount Hiei in 1433. Additionally, the Eikyo Rebellion, led by Kanto kubo Ashikaga Mochiuji, transpired in 1438. In the same year, Yoshinori consolidated the authority of the shogunate by quelling Ashikaga Mochiuji, who took his own life the following year due to growing dissatisfaction with Yoshinori's rule.

During this era, there was heightened contact with China, and Zen Buddhism gained influence, resulting in broad cultural ramifications. For instance, the main hall (Hon-do) at Ikkyu-ji stands today as the oldest extant Tang-style temple in the Yamashiro and Yamato provinces, constructed in 1434 and dedicated by Yoshinori.

Several significant events occurred during Yoshinori's reign: the establishment of the Tosen bugyo in 1434 to oversee foreign affairs; the destruction of the Yasaka Pagoda at Hokanji in Kyoto by fire in 1436, followed by its reconstruction four years later under Yoshinori's patronage; and in 1441, Yoshinori granted the Shimazu clan suzerainty over the Ryūkyū Islands.

In 1432, trade and diplomatic relations between Japan and China were reinstated, a connection that had been severed during Yoshimochi's rule. The Chinese emperor reached out to Japan by sending a missive to the shogunate via the Ryūkyū Islands, to which Yoshinori responded favorably.

Yoshinori's reign also witnessed the establishment of the Tosen-bugyo system in 1434 to mediate overseas trade. This body's functions encompassed safeguarding trading ships in Japanese waters, procuring export goods, mediating between the Muromachi shogunate and shipping interests, and maintaining record-keeping. Notably, the Muromachi shogunate was the first to appoint members of the samurai class to high-ranking positions in its diplomatic bureaucracy.

Yoshinori's rule, however, was marred by his oppressive measures and unpredictable autocratic tendencies. In 1441, he met his demise at the hands of Akamatsu Noriyasu, the son of Akamatsu Mitsusuke, who had invited Yoshinori to a Noh performance at their residence and assassinated him during the evening play. Yoshinori was 48 years old at the time of his assassination. Mitsusuke orchestrated the plot after learning of Yoshinori's intention to bestow three provinces, belonging to Mitsusuke, upon his cousin Akamatsu Sadamura. This decision was influenced by the fact that Sadamura's younger sister had become Yoshinori's concubine and had borne him a son.

In the aftermath, it was decided that Yoshinori's 8-year-old son, Yoshikatsu, would succeed as the new shogun. Mitsusuke had already clashed with the fifth Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi in 1427, leading to Mitsusuke's relocation to Harima province and the burning of his residence in Kyoto. This act further escalated tensions with Yoshimochi, resulting in a deadly pursuit.

While the Ashikaga line persisted through this seventh shogun, the authority of the shoguns gradually waned, leading to the eventual decline of the shogunate. The events surrounding Yoshinori's assassination and betrayal represented a departure from the previous code of military loyalty.

See also

-

Yamagata Masakage

Masakage was one of Takeda Shingen’s most loyal and capable commanders. He was included in the famous list of the “Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen” and also belonged to the inner circle of four especially trusted warlords known as the Shitennō.

-

Yagyu Munenori

Yagyū Munenori began his service under Tokugawa Ieyasu while his father, Yagyū Muneyoshi, was still at his side. In 1600, Munenori took part in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara. As early as 1601, he was appointed a kenjutsu instructor to Tokugawa Hidetada, Ieyasu’s son, who later became the second shogun of the Tokugawa clan.

-

Yagyu Muneyoshi

A samurai from Yamato Province, he was born into a family that had been defeated in its struggle against the Tsutsui clan. Muneyoshi first took part in battle at the age of sixteen. Due to circumstances beyond his control, he was forced to enter the service of the Tsutsui house and later served Miyoshi Tōkei. He subsequently came under the command of Matsunaga Hisahide and in time became a vassal first of Oda and later of Toyotomi.

-

Endo Naozune

Naozune served under Azai Nagamasa and was one of the clan’s leading vassals, renowned for his bravery and determination. He accompanied Nagamasa during his first meeting with Oda Nobunaga and at that time asked for permission to kill Nobunaga, fearing him as an extremely dangerous man; however, Nagamasa did not grant this request.

-

Hosokawa Sumimoto

Sumimoto came from the Hosokawa clan: he was the biological son of Hosokawa Yoshiharu and at the same time the adopted son of Hosokawa Masamoto, the heir of Hosokawa Katsumoto, one of the principal instigators of the Ōnin War. Masamoto was homosexual, never married, and had no children of his own. At first he adopted Sumiyuki, a scion of the aristocratic Kujō family, but this choice provoked dissatisfaction and sharp criticism from the senior vassals of the Hosokawa house. As a result, Masamoto changed his decision and proclaimed Sumimoto as his heir, a representative of a collateral branch of the Hosokawa clan that had long been based in Awa Province on the island of Shikoku. Almost immediately after this, the boy became entangled in a complex and bitter web of political intrigue.

-

Honda Masanobu

Masanobu initially belonged to the retinue of Tokugawa Ieyasu, but later entered the service of Sakai Shōgen, a daimyo and priest from Ueno. This shift automatically made him an enemy of Ieyasu, who was engaged in conflict with the Ikkō-ikki movement in Mikawa Province. After the Ikkō-ikki were defeated in 1564, Masanobu was forced to flee, but in time he returned and once again entered Ieyasu’s service. He did not gain fame as a military commander due to a wound sustained in his youth; nevertheless, over the following fifty years he consistently remained loyal to Ieyasu.

-

Honda Masazumi

Masazumi was the eldest son of Honda Masanobu. From a young age, he served Tokugawa Ieyasu alongside his father, taking part in the affairs of the Tokugawa house and gradually gaining experience in both military and administrative matters. At the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Masazumi was part of the core Tokugawa forces, a clear sign of the high level of trust Ieyasu placed in him. After the campaign ended, he was given a highly sensitive assignment—serving in the guard of the defeated Ishida Mitsunari, one of Tokugawa’s principal enemies—an obligation that required exceptional reliability and caution.

-

Hojo Shigetoki

Hōjō Shigetoki, the third son of Hōjō Yoshitoki, was still very young—only five years old—when his grandfather Tokimasa became the first member of the Hōjō clan to assume the position of shogunal regent.