The Battle of Mikatagahara occurred during Japan's Sengoku period and pitted Takeda Shingen against Tokugawa Ieyasu. This clash took place on January 25, 1573, in Mikatagahara, Tōtōmi Province. Shingen launched an assault on Ieyasu's forces in the Mikatagahara plains, north of Hamamatsu. This engagement happened within the context of Shingen's campaign against Oda Nobunaga, as he sought a passage from Kōfu to Kyoto.

In October 1572, Takeda Shingen, having secured alliances with the Later Hōjō clan of Odawara and the Satomi clan of Awa, and having waited for snow to block northern routes against his rival Uesugi Kenshin, led 30,000 troops from Kōfu into Tōtōmi Province. Simultaneously, Yamagata Masakage led 5,000 soldiers into Mikawa Province, swiftly capturing Yoshida Castle and Futamata Castle.

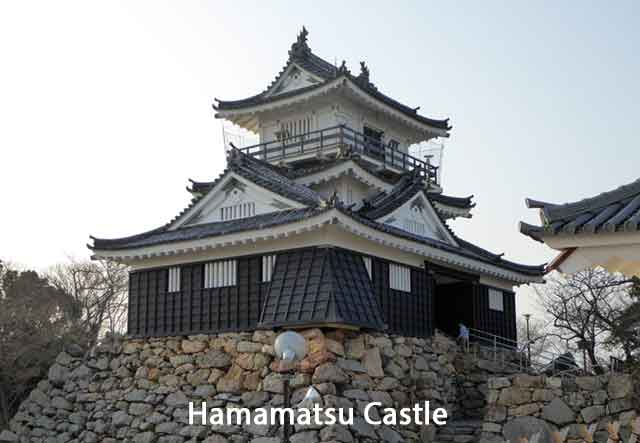

Facing Shingen's advance was Tokugawa Ieyasu, who commanded 8,000 soldiers from Hamamatsu Castle, bolstered by 3,000 reinforcements from Oda Nobunaga. Shingen's aim was not to directly engage Ieyasu or seize Hamamatsu, but rather to conserve his forces for a clash with Nobunaga and a subsequent march to Kyoto.

Despite advice to let the Takeda forces pass, Ieyasu positioned his troops on the elevated Mikatagahara plain north of Hamamatsu. Shingen's troops outnumbered Ieyasu's by three-to-one, and he arranged them in a formation meant to provoke an attack.

As snow fell around 4 PM, Tokugawa's arquebusiers and peasant stone-throwers opened fire on the Takeda formation. Firearms, relatively new in Japanese warfare, were effective against cavalry charges. However, Naitō Masatoyo's vanguard cavalry swiftly overran Tokugawa's right, leading to the collapse of Tokugawa's forces.

Takeda's cavalry exploited this advantage, attacking Oda's reinforcements and charging Tokugawa's rear. Oda's troops were overwhelmed, with key officers killed or fleeing. Although Tokugawa's left resisted encirclement, the center was pushed into a disorderly retreat.

Shingen rested his vanguard and introduced fresh cavalry from the main force. A two-pronged cavalry charge followed, weakening Tokugawa's line. The footsoldier-heavy Takeda main force then drove Tokugawa's battered army into retreat.

Ieyasu attempted to rally his troops but eventually retreated, leaving behind only a few loyal followers. As Ieyasu returned to Hamamatsu Castle, the town was on edge due to rumors of the battle's outcome.

Despite the chaos, Ieyasu ordered the castle gates to remain open and signaled his retreating troops with braziers. In the night, a small Tokugawa force launched a surprise attack on the Takeda camp, causing confusion. Uncertain about Tokugawa's remaining strength and the potential for reinforcements, Shingen withdrew his forces.

The Battle of Mikatagahara showcased Takeda Shingen's skilled cavalry tactics and dealt Tokugawa Ieyasu a significant defeat. While Ieyasu narrowly escaped, the battle resulted in the near-destruction of his army. Shingen did not pursue further attacks on Hamamatsu, as he was later mortally wounded in another engagement and passed away in 1573.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.