On January 4, 1868, the restoration of imperial rule was officially declared, signifying the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu had previously relinquished his authority to the emperor, agreeing to carry out imperial orders. However, although Yoshinobu's resignation created a nominal power vacuum at the highest level of government, the shogunate's administrative structure remained intact. Additionally, the Tokugawa family still held significant influence within the evolving political landscape, which was viewed as unacceptable by hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū.

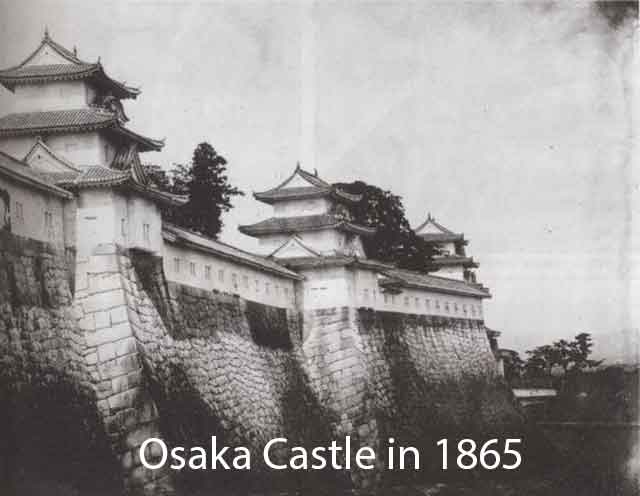

While the majority of Emperor Meiji's fifteen-year-old advisory assembly welcomed the formal declaration of direct rule by the imperial court and leaned toward continuing collaboration with the Tokugawa, Saigō Takamori resorted to physical threats against assembly members, compelling them to order the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands. Initially complying with the court's demands, Yoshinobu later declared on January 17, 1868, that he would not be bound by the restoration proclamation and urged the court to rescind it. Facing provocations from Satsuma's rōnin in Edo and spurred by these events, Yoshinobu, based at Osaka Castle, decided to prepare an attack on Kyōto on January 24. Ostensibly, the goal was to remove the Satsuma and Chōshū elements that dominated the court and free Emperor Meiji from their influence.

Beginning

The battle commenced when the shogunate forces advanced toward Kyoto to deliver a letter from Yoshinobu, warning the Emperor about the plots orchestrated by Satsuma and its court supporters, including Iwakura Tomomi.

The shogunal army, numbering 15,000, outnumbered the Satsuma-Chōshū forces by a ratio of 3 to 1. It consisted mainly of soldiers from the Kuwana and Aizu Domains, with reinforcement from the Shinsengumi irregulars. While some mercenaries were part of their ranks, others, such as the Denshūtai, had received training from French military advisers. The front-line troops were armed with archaic weaponry like pikes and swords. For instance, the Aizu troops comprised a mix of modern soldiers and samurai, similar to a lesser extent in the Satsuma troops. The Bakufu had relatively well-equipped soldiers, while the Chōshū troops were the most modern and organized of them all. According to historian Conrad Totman, in terms of army organization and weaponry, the four main factions ranked as follows: Chōshū was the best, followed by Bakufu infantry, Satsuma, and Aizu with most vassal forces.

The shogunate forces did not display a clear intent to fight, evident from the numerous empty rifles among the vanguard soldiers. Motivation and leadership on the shogunate's side also appeared lacking.

Despite being outnumbered, the Chōshū and Satsuma forces were fully modernized, equipped with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles, and even a Gatling gun. The shogunate forces lagged slightly behind in terms of equipment, although a select elite force had recently undergone training from the French military mission in Japan between 1867 and 1868. The Shogun relied on troops supplied by allied domains, which did not necessarily possess advanced military equipment and tactics, resulting in an army composed of both modern and outdated elements.

The Royal Navy, generally supportive of Satsuma and Chōshū, had a fleet anchored in Osaka harbor, introducing an element of uncertainty. This factor led the shogunate to keep a significant part of its army in reserve within the Osaka garrison instead of committing them fully to the offensive in Kyōto. The presence of foreign naval forces was related to the protection orders for foreign settlements in Hyōgo (modern Kobe) and the recent opening of the ports of Hyōgo and Ōsaka for foreign trade, which occurred three weeks earlier on January 1, 1868. Tokugawa Yoshinobu was incapacitated with a severe chill and could not directly participate in the operations.

First Day of Battle

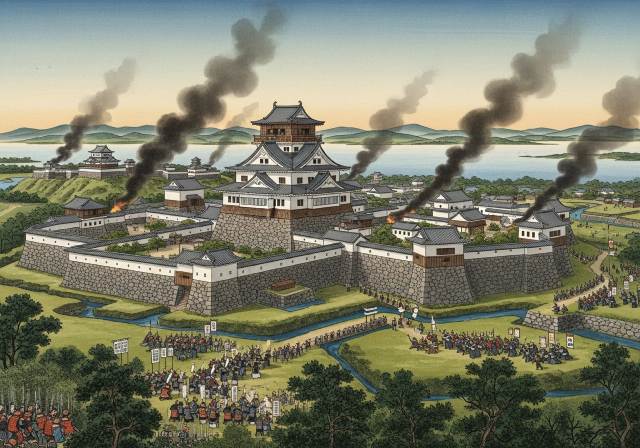

On January 27 1868 Tokugawa Yoshinobu, who was stationed at Osaka Castle south of Kyoto, began mobilizing his troops towards Kyoto using two main roads: the Toba road and the Fushimi road. Approximately 13,000 troops were on the move, although they were spread out, with around 8,500 participating in the action at Toba-Fushimi. Takenaka Shigekata was the overall commander of the operation.

The shogunate forces, led by Vice-Commander Ōkubo Tadayuki, moved in the direction of Toba with a total of 2,000 to 2,500 troops. At around 17:00, the shogunate vanguard, primarily consisting of about 400 men from the Mimawarigumi armed with pikes and some firearms, under the command of Sasaki Tadasaburo, approached a barrier post manned by Satsuma forces at Koeda Bridge in Toba (now part of Minami-ku, Kyoto). They were followed by two infantry battalions, with their rifles empty as they did not anticipate a fight, under the command of Tokuyama Kōtarō, and further south by eight companies from Kuwana with four cannons. Some troops from Matsuyama and Takamatsu, as well as a few others, were also participating, but shogunate cavalry and artillery were seemingly absent. Positioned ahead of them were approximately 900 entrenched Satsuma troops with four cannons.

After being denied permission to pass peacefully, the Satsuma forces opened fire from the flank, marking the first shots of the Boshin War. A Satsuma shell exploded near a gun carriage next to shogunal commander Takigawa Tomotaka's horse, causing the horse to panic and throw Takigawa off before bolting. The frightened horse ran uncontrollably, creating chaos and confusion within the shogunate column. The Satsuma attack was fierce and quickly threw the shogunate troops into disarray and retreat.

Sasaki ordered his men to charge the Satsuma gunners, but since the Mimawarigumi was armed only with spears and swords, they suffered heavy casualties. However, the Kuwana forces and a unit under Kubota Shigeaki managed to hold their ground, prolonging the skirmish without a clear outcome. As the shogunate troops retreated, they set fire to various houses, which inadvertently made it easier for Satsuma snipers to target them. The situation eventually stabilized during the night when reinforcements from Kuwana arrived.

On the same day, the Satsuma-Chōshū forces further southeast in Fushimi also engaged the shogunate forces in their area, but the encounter ended inconclusively. The Satsuma-Chōshū forces began firing upon the shogunate forces upon hearing the sound of cannons from the Toba area.

The second day of the battle

On January 28, Iwakura Tomomi delivered orders from Emperor Meiji to Saigō Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi. These orders declared Tokugawa Yoshinobu and his followers as enemies of the court and authorized their suppression through military force. The Emperor also granted the use of the Imperial brocade banners, which had been prepared in advance by Ōkubo Toshimichi and stored in the Chōshū domain and the Satsuma Kyoto residence, awaiting the right moment to be utilized.

Furthermore, Imperial Prince Yoshiaki, a 22-year-old who had previously lived as a Buddhist monk at the Ninna-ji temple, was appointed as the nominal commander in chief of the army. Despite lacking military experience, this appointment effectively transformed the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance forces into an Imperial army (kangun). This development proved to be a potent psychological weapon, causing confusion and disarray among the shogunal forces. Firing upon the Imperial army would automatically brand the perpetrator as a traitor to the emperor.

Simultaneously, the Battle of Awa occurred on the Inland Sea. This naval engagement marked the first clash between modern fleets in Japan. While it resulted in a minor shogunate victory over a Satsuma fleet, the battle had little impact on the unfolding events of the land conflict.

The forces that had previously been engaged in Fushimi, consisting of Aizu troops, Shinsengumi, and Yūgekitai guerrilla troops, were once again attacked by Satsuma and Chōshū troops at Takasegawa and Ujigawa on the morning of the 28th. After a fierce struggle, they were compelled to retreat towards Yodo Castle.

The third day of the battle

On January 30, Tokugawa Yoshinobu convened a meeting at Osaka Castle with his advisors and military leaders to strategize. In an attempt to boost morale, he announced his intention to personally lead the bakufu forces. However, that evening, Yoshinobu secretly left Osaka Castle in the company of the daimyōs from Aizu and Kuwana, aiming to escape back to Edo on the shogunate warship Kaiyō Maru.

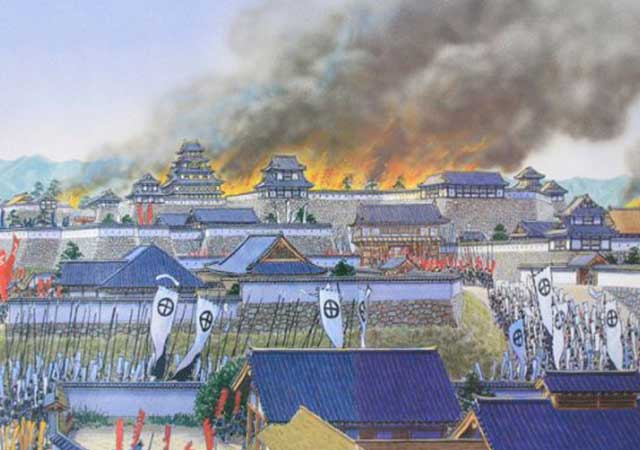

Since the Kaiyō Maru had not yet arrived, Yoshinobu sought refuge for the night on an American warship, the USS Iroquois, anchored in Osaka Bay. The Kaiyō Maru finally arrived the following day. When news reached the remaining shogunate forces that the shōgun had deserted them, they abandoned Osaka Castle. Later, the castle was surrendered to the Imperial forces without resistance. Yoshinobu claimed that he had been disheartened by the Imperial approval bestowed upon Satsuma and Chōshū's actions, and the appearance of the brocade banner had further eroded his will to fight.

The aftermath of the Battle of Toba–Fushimi had repercussions that exceeded its relatively small scale. The Tokugawa bakufu suffered a significant blow to its prestige and morale, leading many previously neutral daimyōs to declare their allegiance to the Emperor and offer military support. Moreover, Tokugawa Yoshinobu's ill-fated attempt to regain control silenced factions within the new imperial government that had favored a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.