The Battle of Hakodate, also known as the Battle of Goryokaku, took place in Japan from December 4, 1868, to June 27, 1869. It was fought between the remnants of the Tokugawa shogunate army, which had formed the rebel Ezo Republic, and the armies of the newly formed Imperial government. The Imperial forces were composed mainly of troops from the Chōshū and Satsuma domains. This battle was the final stage of the Boshin War and occurred in the northern Japanese island of Hokkaidō, specifically around Hakodate. In Japanese, it is also referred to as "Goryokaku no tatakai."

The Boshin War broke out in 1868 between forces favoring the restoration of political authority to the Emperor and the government of the Tokugawa shogunate. The Meiji government defeated the Shōgun's forces at the Battle of Toba–Fushimi and subsequently occupied the Shōgun's capital at Edo.

Enomoto Takeaki, vice-commander of the Shogunate Navy, refused to hand over his fleet to the new government and departed Shinagawa on August 20, 1868, with four steam warships (Kaiyō, Kaiten, Banryū, Chiyodagata) and four steam transports (Kanrin Maru, Mikaho, Shinsoku, Chōgei), along with 2,000 sailors, 36 members of the "Yugekitai" (guerrilla corps) headed by Iba Hachiro, several officials of the former Bakufu government including the vice-commander in chief of the Shogunate Army Matsudaira Taro, Nakajima Saburozuke, and members of the French Military Mission to Japan, headed by Jules Brunet.

On August 21, the fleet encountered a typhoon off Chōshi, in which Mikaho was lost and Kanrin Maru, heavily damaged, was forced to turn back and was later captured at Shimizu.

The remaining ships of Enomoto Takeaki's fleet arrived at Sendai harbor on August 26, which was a center of the Northern Coalition against the newly formed Imperial government. However, the Imperial troops continued to advance north and took over the castle of Wakamatsu, making Sendai's position untenable. On October 12, 1868, the fleet left Sendai with two more ships and about 1,000 more troops, including former Bakufu troops, Shinsengumi troops, and Yugekitai, along with several French advisors who had arrived overland.

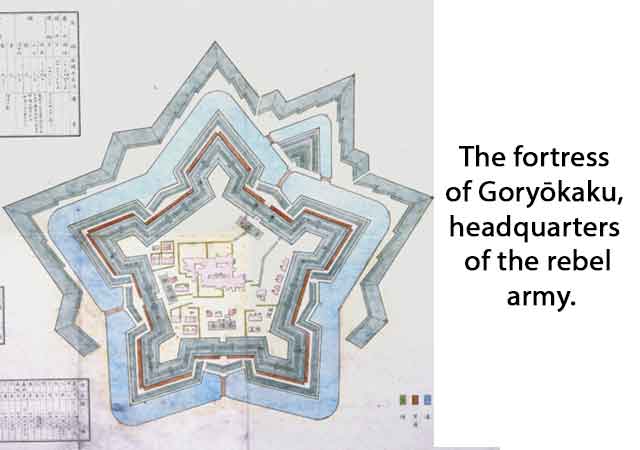

Enomoto and his rebels, with a force of around 3,000, arrived in Hokkaido in October 1868, landing on Washinoki Bay behind Hakodate on October 20. They eliminated local resistance from the Matsumae Domain, which had declared its loyalty to the Meiji government, and occupied the Goryokaku fortress on October 26, making it their command center.

The rebels then launched expeditions to take full control of the southern peninsula of Hokkaido. On November 5, Hijikata and his 800 troops, supported by the warships Kaiten and Banryo, occupied the castle of Matsumae. On November 14, Hijikata and Matsudaira converged on the city of Esashi with the added support of the flagship Kaiyo Maru and the transport ship Shinsoku. However, Kaiyo Maru was lost in a tempest near Esashi, and Shinsoku was lost as it tried to rescue Kaiyo Maru, dealing a terrible blow to the rebel forces.

On December 25, after eliminating all local resistance, the rebels declared the establishment of the Ezo Republic, with Enomoto Takeaki as its President. The government was organized in a manner similar to that of the United States. However, the Meiji government in Tokyo refused to recognize the breakaway republic.

The Ezo Republic established a defense network around Hakodate in preparation for an attack by the new Imperial government's troops. The Ezo troops were led by a combination of French and Japanese officers, with Ōtori Keisuke as Commander in chief and Jules Brunet as his second-in-command. Each of the four brigades was commanded by a French officer, including Fortant, Marlin, André Cazeneuve, and Bouffier, who were each supported by eight Japanese commanders. Two ex-French Navy officers, Eugène Collache and Henri Nicol, also joined the Ezo Republic, with Collache tasked with building fortified defenses along the volcanic mountains around Hakodate and Nicol in charge of re-organizing the Navy.

Meanwhile, the Meiji government rapidly assembled an Imperial fleet centered around the ironclad warship Kōtetsu, which they had acquired from the United States. Other ships in the fleet included Kasuga, Hiryū, Teibō, Yōshun, and Mōshun, which had been supplied by the fiefs of Saga, Chōshū, and Satsuma. The fleet left Tokyo on March 9, 1869, and headed north.

The Imperial fleet dispatched three warships for a surprise attack, known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The Kaiten carried the elite Shinsengumi and ex-French Navy officer Henri Nicol, while the warship Banryu had ex-French officer Clateau on board, and the warship Takao had ex-French Navy officer Eugène Collache. To create surprise, the Kaiten entered Miyako harbor flying an American flag, but quickly raised the Ezo Republic flag seconds before boarding the Kōtetsu. The crew of Kōtetsu repelled the attack with a Gatling gun, resulting in significant losses to the attackers. The two Ezo warships retreated back to Hokkaidō, but the Takao was pursued and beached.

Finally, on April 9, 1869, the Imperial troops, numbering 7,000, landed on Hokkaidō and gradually took over various defensive positions, with the final battle taking place around the fortress of Goryōkaku and Benten Daiba near the city of Hakodate. The Naval Battle of Hakodate Bay, Japan's first major naval engagement between two modern navies, occurred towards the end of the conflict in May 1869. Before the final surrender in June 1869, the Ezo Republic's French military advisors escaped to a French Navy warship stationed in Hakodate Bay, the Coëtlogon, and returned to Yokohama before eventually returning to France.

On June 27, 1869, the military of Ezo Republic surrendered to the Meiji government, having lost almost half their numbers and most of their ships. This marked the end of the old feudal regime in Japan and the end of armed resistance to the Meiji Restoration. Several leaders of the rebellion were imprisoned for a few years before being rehabilitated and continuing with successful political careers in the new unified Japan. The Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established in July 1869 and incorporated many combatants and ships from the Battle of Hakodate.

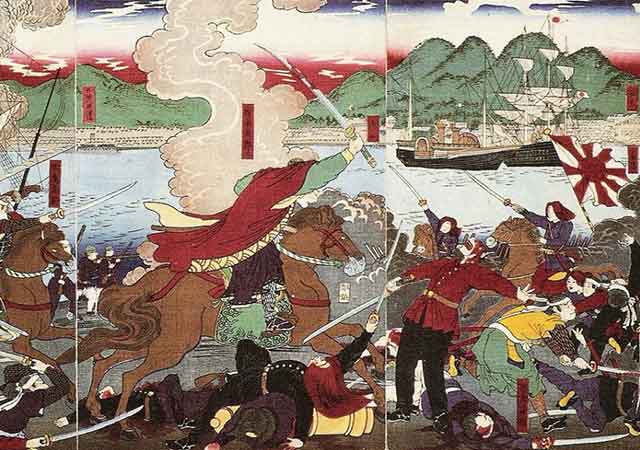

Tōgō Heihachirō, who later became a famous admiral and hero of the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, participated in the Battle of Hakodate as a gunner on board the paddle steam warship Kasuga. Although the battle involved some of the most modern armament of the time, such as steam warships, an ironclad warship, Gatling guns, and Armstrong guns, many Japanese depictions of the battle during the few years after the Meiji Restoration offered an anachronistic representation of traditional samurai fighting with their swords, possibly to romanticize the conflict or downplay the amount of modernization already achieved during the Bakumatsu period (1853–1868).

The modernization of Japan actually started significantly earlier, around 1853, during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate (the Bakumatsu period). The 1869 Battle of Hakodate shows two sophisticated adversaries in an essentially modern conflict where steam power and guns played a key role, although some elements of traditional combat remained. Western scientific and technological knowledge had already been entering Japan since around 1720 through rangaku, the study of Western sciences, and since 1853, the Tokugawa shogunate had been actively modernizing the country and opening it to foreign influence.

See also

-

The Siege of Hara Castle

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, which culminated in the siege of Hara Castle, was the last major uprising of the Edo period and had serious political consequences.

-

Battle of Tennoji

The confrontation between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori during the “Osaka Winter Campaign” ended with the signing of a peace treaty. On January 22, 1615, the day after the treaty was signed, Ieyasu pretended to disband his army. In reality, this meant that the Shimazu forces withdrew to the nearest port. On the same day, almost the entire Tokugawa army began filling in the outer moat.

-

Siege of Shuri Castle

The Ryukyu Kingdom was established in 1429 on Okinawa, the largest island of the Ryukyu (Nansei) archipelago, as a result of the military unification of three rival kingdoms. In the following years, the state's control spread to all the islands of the archipelago.

-

The Siege of Fushimi Castle

Fushimi can perhaps be considered one of the most “unfortunate” castles of the Sengoku Jidai period. The original castle was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the southeast of Kyoto in 1594 as his residence in the imperial city.

-

The Siege of Otsu Castle

The siege of Otsu Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign, during which the so-called Eastern Coalition, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, fought against the Western Coalition, led by Ishida Mitsunari. Otsu Castle was built in 1586 by order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi near the capital Kyoto, on the site of the dismantled Sakamoto Castle. It belonged to the type of “water castles” — mizujō — as one side of it faced Japan's largest lake, Lake Biwa, and it was surrounded by a system of moats filled with lake water, which made the fortress resemble an island.

-

The Siege of Shiroishi Castle

The siege of Shiroishi Castle was part of the Sekigahara campaign and took place several months before the decisive battle of Sekigahara. The daimyo of Aizu Province, Uesugi Kagekatsu, posed a serious threat to Tokugawa Ieyasu's plans to defeat the Western Coalition, and Ieyasu decided to curb his actions with the help of his northern vassals. To this end, he ordered Date Masamune to invade the province of Aizu and capture Shiroishi Castle.

-

The Second Siege of Jinju Castle

During the two Korean campaigns of the 16th century, the Japanese repeatedly had to capture enemy fortresses and defend occupied or constructed fortifications from the combined Korean and Chinese forces. Among all the operations of that time, the second siege of Jinju Castle is considered the most interesting from the point of view of siege warfare.

-

The Siege of Takamatsu Castle

The siege of Takamatsu Castle in Bitchu Province is considered the first mizuzeme, or “water siege,” in Japanese history. Until then, such an original tactic had never been used.