When Westerners think of Japanese swords, they often picture the iconic curved blades like the katana. However, in terms of historical precedence and prestige, it would be more accurate to reverse this image—the tachi predates the katana and traditionally held a higher status.

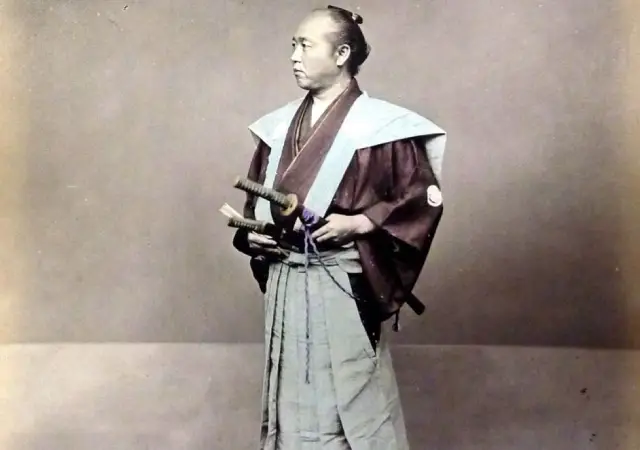

Well before Japan’s tumultuous Warring States period, the tachi served as both the primary weapon and a ceremonial emblem of mounted warriors. Classical illustrations of famous generals and legendary heroes consistently depict them wearing tachi swords at their hips—whether on horseback, aboard boats, or standing on solid ground. The tachi was always present, its long, curved blade a defining part of a warrior’s silhouette. In earlier times, scabbards were often adorned with fur from animals like boars, tigers, or bears, though this fashion faded with time and changing tastes. Later samurai, during the Ashikaga, Oda, and Tokugawa eras, adopted a simpler aesthetic.

In contrast, the katana was typically carried by lower-ranking foot soldiers and civilians—including, at times, outlaws. The tachi remained the weapon of high-ranking samurai, but both swords had their uses depending on context. Still, these distinctions weren't rigid laws—rather, general trends. A fully armored warlord carrying a katana might appear as oddly dressed as a common townsman wearing an elaborate tachi over a tattered kimono.

While the blades of the tachi and katana are similar in shape, key differences exist. The tachi is typically longer and features a deeper curve, making it especially well-suited for mounted combat. Cavalry combat required slicing at enemies from above, and the tachi’s length helped reach opponents on foot. This curved, elongated design also appeared in the sabers of other horse-riding cultures, like the Mongols and Persians. The function defined the form.

The tachi typically featured long, narrow, and aggressive blades. Its golden era was during the Kamakura period, a time of frequent warfare that demanded quality without the mass production that would later characterize the Muromachi era.

he tachi’s suspension system was particularly elegant and functional. It was worn edge-down, suspended high on the left side by a cord, allowing for easy movement—running, mounting a horse, or even tumbling—without the sword getting in the way. This was a major improvement over European styles, where long swords dragged on the ground or posed hazards to people nearby.

Early tachi also had distinctive handles, often disproportionate by today’s standards but practical for their original wielders. Field swords known as "no-tachi" were so large they couldn't be worn at the hip at all and were instead carried across the back or over the shoulder by powerful infantrymen, designed specifically to counter cavalry.

Some tachi had unique, archaic grips without the later common silk braid. Instead, leather—such as rayskin (Same Kawa)—was nailed directly to the handle, often with decorative metal plaques. This style was reserved for high-status ceremonial swords and rare, ornamental pieces.

By the Tokugawa period, the tachi had lost its battlefield role and survived mostly as a ceremonial accessory. During this peaceful era, artisans created exquisite decorative swords—many of which inspire modern reproductions. However, this also gave rise to a black market of forgeries, with craftsmen crafting ornate swords hiding inferior blades. These “kazari-tachi” (decorative tachi) were essentially fashion accessories, similar to the ornamental, non-functional swords of European nobility.

Unlike the tachi, the katana never fell into the role of mere costume. Though noblemen carried it, it retained its purpose as a combat weapon. As warfare shifted from open battlefields to duels and skirmishes in city streets and rural paths, speed and precision became more valuable than brute force. Samurai now fought in light clothing or kimono, and the katana was perfectly adapted to this.

The katana was worn edge-up, tucked into the waist in a slightly diagonal position, allowing for lightning-fast draws and strikes—especially using the "iai" technique, where the blade is drawn and cuts in a single motion. The shorter wakizashi was typically worn alongside it. This method of wear was practical and secure, even allowing for acrobatic movement.

Katana blades are usually shorter and less curved than tachi, optimized for foot combat. A long, heavily curved blade would be cumbersome for a pedestrian—its tip might hit the ground, costing precious time in a duel. A straighter blade is more efficient for thrusting.

Over time, experience shaped the katana into the form we know today: a blade length of around 75 cm, with handles measuring 25–30 cm. These dimensions varied depending on the height and arm length of the user, but the essence remained—a sword designed for precision, speed, and survival.

See also

-

Sojutsu - The Art of the Spear

Sojutsu is a traditional Japanese martial art dedicated to the mastery of the yari spear. It is considered the second most important martial art of medieval Japan after swordsmanship.

-

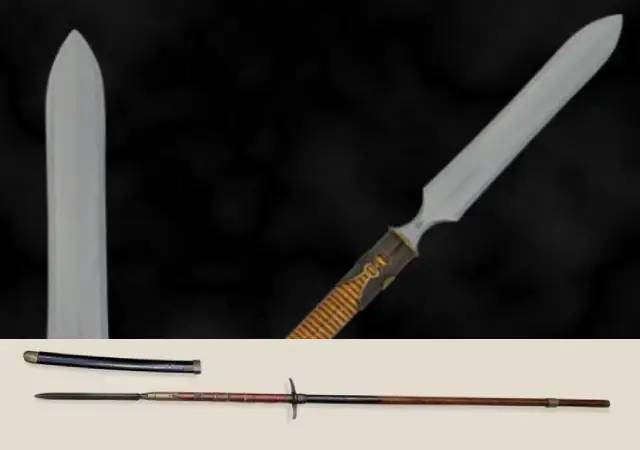

Yari

Yari is one of the traditional Japanese cold weapons (nihonto), which is a spear with a straight tip. The art of wielding a yari is known as sojutsu, a spear fighting technique.

-

Wakizashi and tanto

In the history of Japanese edged weapons there are objects that border between the concepts of “sword” and “knife”. This is especially true of the wakizashi, a short sword traditionally carried by samurai along with the katana, and the tanto, a combat knife popular among a wide range of social classes. Both items were worn behind the belt, had a short blade, and were used in close combat. However, there is a fundamental difference between the two, and it goes far beyond simple blade length.

-

Daisho: The Origins and Evolution of the Samurai Sword Pair

The term "daisho" finds its roots in the combination of two Japanese words: "daito," denoting a long sword, and "shoto," signifying a short sword. The combination of the words daito and shoto made the word. Daisho referred to the practice of wearing both a long and short katana together, regardless of their matching characteristics. While the classic depiction of daisho involves a katana and wakizashi (or tanto) in matching koshirae, any pairing of a longer sword with a tanto can also be considered a daisho. It later came to mean two swords with coordinated fittings. While having blades from the same swordsmith was an option, it was not a requirement for a pair to be classified as a daisho, as this would have been a more costly choice for a samurai.

-

Tanto

The Tanto knife is a traditional Japanese dagger that was once an integral part of the samurai warrior’s arsenal. It is known for its unique shape and cutting ability, and it is still revered by many martial artists and knife enthusiasts today.

-

Tachi

The samurai sword known as Tachi is one of the most iconic weapons in Japanese history. Its unique design and construction made it a popular choice among samurai warriors, and it played a significant role in many battles throughout Japan's history.

-

Nagitana

The Nagitana is a formidable weapon that was used by the samurai during feudal Japan. It was a polearm that combined the elements of a spear and a sword, making it a versatile weapon that was effective both at long range and in close combat. In this article, we will explore the history, construction, characteristics, and usage of the Nagitana.

-

Wakizashi

How did Wakizashi come about

The wakizashi, also known as the companion sword, is a traditional Japanese short sword that was widely used by the samurai warriors during the feudal era in Japan. This versatile sword has a long and rich history, and has played an important role in Japanese culture and warfare for centuries.